All Activity

- Past hour

-

Chevrolet is trying to do patriotism without politics in its America250 ad

Chevrolet’s latest splashy ad has all the hallmarks of a campaign strategically tied to America’s 250th anniversary. There’s the modern interpretation of a 75-year-old jingle that’s sung by an up-and-coming country singer. A bird’s-eye view of a pickup truck atop a natural landmark in Utah. A television debut on February 6 during the opening ceremony for the Winter Olympics. In every choice, Chevrolet is carving out friendly, apolitical terrain at a moment when Americans have mixed feelings about such patriotism. A record-low 58% of U.S. adults say they are “extremely” or “very” proud to be American, according to a Gallup survey from last year. That’s down 9 percentage points from 2024. “It feels like modern patriotism has to walk a fine line between celebrating what’s great about America but also being careful not to anchor to just glib symbols and slogans that potentially could be dividing or polarizing,” Paul Frampton-Calero, CEO of digital marketing agency the Goodway Group, tells Fast Company. A calendar built for America250 The United States Semiquincentennial—America250, A250, Quarter Millennium—whatever one would like to call it, may be too enticing for marketers to ignore. This year’s calendar is overstuffed with holidays like Independence Day and Memorial Day, as well as major sporting events like the Winter Olympics and the FIFA World Cup, which align nicely with patriotism. “There’s just a little bit more attention on America, American pride, and what the Olympics spirit is about,” Steve Majoros, Chevrolet’s chief marketing officer, tells Fast Company. Throughout 2026, Chevrolet will revisit some of the auto brand’s classic campaigns and update them with a modern interpretation that coincides with major American moments, including the beginning of the baseball season this spring and Independence Day. Brands rush in, politics close behind The allure of the semiquincentennial has led large corporations including Amazon, Coca-Cola, and Cracker Barrel to sponsor the bipartisan “America250” initiative, which is planning programming to promote the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Patriotism is also a major theme in Budweiser’s Super Bowl campaign called “American Icons,” starring a galloping Clydesdale and flying bald eagle as “Free Bird” by Lynyrd Skynyrd roars in the background. But America’s anniversary was also the focus of a “traditional values” marketing campaign promoting faith and marriage between a “husband and wife” funded by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank. That spot aired during the NFL playoffs. A generational divide in American pride The Gallup poll showed less U.S. pride among Democrats and even some independents, which may not be a surprise given that the Republican Party fully controls all branches of government in Washington, D.C. But there could also be a generational divide that brands may need to consider when activating around America250. When contextual advertising platform Chicory surveyed 1,000 U.S. consumers last month, it found that while 58% of Americans plan to celebrate the nation’s anniversary, enthusiasm was far weaker for younger adults. “There’s a lot more hesitation within the Gen Z cohort,” Yuni Baker-Saito, cofounder and CEO of Chicory, tells Fast Company. The risk calculus for CMOs Marketers who opt into messaging that celebrates the birth of the nation will largely aim to avoid wading too far into cultural war controversies that sparked boycotts and fiery criticism for marketing initiatives from Bud Light, American Eagle, and Cracker Barrel. Americans are divided on whether they want corporate entities to weigh in on political or social issues, and CEOs are also wary. Target and Starbucks have been perennial targets for right-leaning activists for their more “left” positioning. But as they have moved to carve out more central and moderate corporate identities, both retailers have also angered more liberal-leaning consumers who have also called for boycotts. Risk-averse CMOs will have to be thoughtful about every creative decision they make for any patriotism-themed ads this year. “The board wakes up when choosing the wrong ad, the wrong song, or the wrong talent,” says Frampton-Calero. He believes that Chevrolet’s classic branding, which is frequently anchored in freedom of the moment, family, and road trips, avoids polarization. “I think they’re quite a good example of staying on the right side of patriotism that connects into personal, collective well-being that resonates to an American,” Frampton-Calero adds. Nostalgia as a safe bridge Nostalgic elements of Chevrolet’s “See the USA in your Chevrolet” include a song first performed by actress and singer Dinah Shore on her namesake TV variety show. The new version is sung by country artist Brooke Lee. Most new viewers won’t make the connection to the old reference, but according to the company, it ties into the brand’s musical lineage. “Chevrolet” or “Chevy” has been name-checked in more than 1,000 songs, including “Tim McGraw” by Taylor Swift. Airlifting a 2026 Chevrolet Silverado ZR2 to the top of Castle Rock in Utah for the ad spot is also a nod to two of the brand’s past campaigns, when it put a Chevy Impala atop the 400-foot rock in TV and print advertisements that aired in 1964 and 1973. Universal values, global appeal Majoros says Chevrolet’s patriotic-forward campaign rests on universal themes that most Americans can agree on, including “hard work, hope, optimism, opportunity, building families, communities, neighborhoods, and creating memories.” Many of those values also surface in research that’s conducted in markets ranging from China to South America. The brand’s current slogan, “Together let’s drive,” is also intentional wording that allows Chevrolet to “step to the side of that divisiveness,” he adds. When asked about the Gallup poll, Majoros sees opportunity. “That means there’s 42% of people who are thirsty to connect to something and who want to be part of something,” he says. “The majority of people probably fall in that big, huge middle. If we can be the kind of a brand that speaks to the things that people are thinking about—and longing for—I think that number would be much higher.” View the full article

-

These 5 brands are winning the Super Bowl pregame push

The Super Bowl is mere days away and chances are you’ve seen most of the ads already. Right? Let’s rewind for a 10-second Super Bowl ad history lesson that goes like this: In 2011, Volkswagen decided to drop its full ad—called “The Force”—online the Wednesday before the Super Bowl. This was brand marketer blasphemy! But it worked. Ever since, more and more brands began dropping ads earlier and earlier, which then evolved into creating teasers for the ads to run even earlier. If you’re confused as to why this happens, don’t sweat it, even Christopher Walken wasn’t sure in BMW’s 2024 Super Bowl teaser. Super Bowl commercials are no longer just Super Bowl commercials. They are Super Bowl campaigns that run for weeks before and after the game. Now, say it in your best Walken voice, “Why would they do that?” So much more than $8M The last time the Patriots and Seahawks met in the Super Bowl in 2015, 30 seconds of commercial time on NBC went for about $4.4 million. This year, a 30-second spot averaged $8 million, plus another $8 million in required spend for other NBC sports broadcasting and the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics, according to Ad Age. That price tag could go as high as $10 million, when you consider expanding that to Peacock and Telemundo. And that’s all before you spend a dime on actually making the ad. With this much at stake, brands are investing even more to extend the life of their Super Bowl ads. Which is why we start hearing about them in early to mid-January. Given the sheer size and scale of the Super Bowl season, we decided to do a power-rankings list to break down the five brands we believe have the most momentum heading into the game. 1. Budweiser Created by BBDO New York, “American Icons” traces the friendship and bond between a foal and an eaglet. I mean, come on. Bud’s done it before with a puppy in 2014, so why not adapt the audience-winning concept to celebrate Bud’s 150th (horse!) and America’s 250th (eagle!) anniversaries? Creative data firm Daivid analyzed early-release Super Bowl commercials to identify those that are most likely to resonate with consumers. This spot topped its pregame rankings after generating intense positive emotions among 54% of viewers—11% higher than the U.S. average. It was also 155% more likely than the average ad to evoke intense nostalgia, and nearly twice as likely to generate strong feelings of warmth (+99%). Per Daivid’s analysis, the spot drove elevated feelings of adoration for its use of animal characters (+80%) and joy (+71%)—and maintained above-average attention throughout. Budweiser consistently puts out top-rated ads, from comedy with the frogs and “Wassup” to all the variations on heartwarming puppies, dogs, and horses. It’s so iconic, even Jason Kelce’s Garage Beer made a funny Clydesdales spoof for this year’s game. Here Bud is going full ’Murica, but manages to thread the nonpartisan needle to find a sweet spot that everyone can enjoy. Just don’t be surprised if the guy next to you spontaneously holds his light in the air. 2. Pepsi Back in 1995, Pepsi dropped an iconic Super Bowl ad in which a Coke delivery truck driver takes an impromptu Pepsi Challenge in a diner. Many brands shy away from directly challenging their biggest rivals, especially on such a big ad stage, for fear of giving any oxygen to another brand. But Pepsi famously rode the Pepsi Challenge to success, constantly trolling Coca-Cola and scoring an impressive eight spots in the USA Today Ad Meter’s 10 Best Super Bowl Ads of the 1990s. Here, the brand goes back to the well and puts Coke’s famous polar bear mascot in the delivery truck driver’s role—another symbol of Coke choosing Pepsi. The simplicity may seem like a waste of Taika Waititi’s talents, but it’s going to score big with Super Bowl audiences. According to the Daivid survey, the spot is 56% more likely to make viewers laugh than the average ad, and most likely to make viewers’ mouths water. 3. Rocket and Redfin Here’s an idea: Let’s get one of the biggest pop stars on the planet to reimagine a childhood classic. Right then and there you have a potential winner. That’s exactly what Rocket Mortgage and Redfin’s teaser featuring behind-the-scenes footage of Lady Gaga singing Fred Rogers’s “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” does. This looks like it might be one of those vibe-shift ads—the one people shush the party for because they want to hear it. The Daivid data backs this up, reporting it generated the most intense positive emotions of any teaser or full Super Bowl ad so far. 4. State Farm Just a Super Bowl shopping list of good stuff here: funny? Danny McBride and Keegan-Michael Key. (Check.) Celebrity? Hailee Steinfeld and Katseye. (Check.) Nostalgic sing-along? Bon Jovi remix. (Check.) And the teasers with McBride and Key doing full ads for Halfway There Insurance are also a nice touch. This continues State Farm’s long-running formula for its Super Bowl ad campaigns. In 2024, it was Arnold Schwarzenegger making the brand’s tagline his own with “Like a Good Neighbaaa.” Last year, it was Jason Bateman becoming a less-than-ideal version of Batman. (The brand actually pulled that spot out of the big game due to sensitivities around the Los Angeles wildfires, but ran it a month later for March Madness.) CMO Kristyn Cook told me the strategy has been working. “Insurance is very complex, and we’re able to break it down in a way that’s humorous enough for people to hopefully pay attention and get them thinking about it,” she says. “Do I have the right coverage? Are people going to be there when I need them? Just trying to create those opportunities for people to think about it and then drive action. It’s a formula for us, but it’s a big stage and we want to do it really well with the standards that we have that are very high.” 5. Novartis I’m not saying this spot involves a poop joke, but it’s pretty close. And it’s not going full Raisin Bran, but we’re in the vicinity. Directed by Eric Wareheim, “Relax Your Tight End” stars celebrated NFL tight ends and a playful double entendre for prostate cancer screening awareness. Set to Enya’s “Only Time” (shout-out to Volvo and Van Damme), getting big tough guys talking about an uncomfortable health issue is important. Showing them all relaxing their buns when they hear it’s just a blood test will definitely clinch (clench?) some major attention. According to Daivid, so far the campaign has generated intense positive emotions among 52.6% of viewers—8% higher than the U.S. norm. View the full article

-

How the WM Phoenix Open’s stadium hole became a blueprint for event design

On most golf courses, silence is sacred. At the WM Phoenix Open’s 16th hole, noise is the point. Every year, tens of thousands of fans pack into a stadium-like enclosure at TPC Scottsdale, turning a short par 3 into one of the most recognizable—and rowdiest—settings in sports. Missed putts are booed. Holes in one trigger cascades of beer. The atmosphere is closer to a college football rivalry than a PGA Tour stop. But as iconic as the 16th hole has become, its future wasn’t guaranteed by tradition alone. Behind the spectacle, the structure itself had reached a limit—architecturally, operationally, and environmentally. “We made the decision that that was as good as that structure was going to get,” says Jason Eisenberg, the 2026 tournament chairman. “If we want to continue to have an amazing fan experience, if we want fans to come back and see something new, we were going to have to elevate that experience.” That realization sparked a full redesign of the 16th hole—one that goes far beyond aesthetics. What’s emerging ahead of the 2026 tournament is a case study in how physical design, systems design, and cultural design can align to quietly change how large-scale events are built and run. The result isn’t just a louder or flashier venue. It’s a reusable, modular structure designed to last decades, embedded within one of the world’s largest certified zero-waste sporting events—and supported by a culture that treats experimentation as essential, not optional. TPC Scottsdale is a publicly owned course, operated by the City of Scottsdale and host to the Phoenix Open for decades. Its ownership structure—and the regulatory constraints that come with it—means that even the tournament’s most iconic spaces must be built to appear and disappear each year. Design Change Like every structure on the PGA Tour, the 16th hole at the WM Phoenix Open is built from scratch each year and dismantled once the tournament ends. What makes it unusual isn’t that it’s rebuilt annually, but that it has reached the practical limits of how much a temporary structure can evolve without fundamentally changing how it’s designed. “Every year, we would add to the 16th hole,” says Danny Ellis, senior vice president of sales and business development at InProduction, the company that has built the structure for nearly three decades. “Every year it would take on another section, another layer. Eventually, we reached a point where the footprint couldn’t expand anymore.” By 2020, the grandstand had reached three levels wrapping fully around the hole. The Thunderbirds, who operate the tournament, were satisfied with its location and scale. What wasn’t sustainable was how it was built. The structure relied heavily on timber and cut plywood, requiring all three levels to be recut, modified, and refinished every year—a process that was increasingly misaligned with both modern fan expectation and the tournament’s zero-waste ambitions. Across the PGA Tour, temporary construction is the norm. Each week, courses are outfitted with general-admission grandstands, hospitality structures, media centers, broadcast towers, volunteer headquarters, and fan walkways, all designed to exist for a single event. A typical Tour stop might involve roughly 200,000 square feet of temporary flooring spread across an entire course. At most tournaments, those elements are distributed across multiple holes; at the WM Phoenix Open, they are concentrated, layered, and intensified within a single one. From disposable to reusable The 16th hole alone doubles that footprint. With approximately 400,000 square feet of flooring contained within a single hole, it operates less like a golf installation and more like a stadium build—rebuilt annually, but engineered for one of the most densely packed fan environments in sports. By both scale and construction method, the 16th hole now occupies a category of its own—without direct analogue on the PGA Tour or at any other sporting event worldwide. The redesign addresses that mismatch by shifting from disposable construction to modular reuse. Levels two and three have been rebuilt using fully modular decking systems encased in metal frames, eliminating the need for annual cutting on two-thirds of the structure. Only the first level still relies on plywood, reducing construction—related waste at the 16th hole by roughly two-thirds compared to previous builds. Designing for reuse also changed the structure’s internal logic. Long-span engineering allows for wider interior spaces, fewer vertical supports, and cleaner sight lines—subtle changes that have an outsized impact on how fans move through and experience the space. Robert MacIntyre “The spans we created inside literally took out every other leg in the structure,” Ellis says. “Before, we had a support every 10 feet. Now, it’s every 20 feet.” The materials themselves reflect a shift toward permanence without permanence. The structure is built from galvanized steel and aluminum, and incorporates I-beams, bar joists, and glass guardrails—components typically associated with fixed buildings rather than temporary events. Reducing material use Dismantling and load-out takes roughly eight weeks, after which the modular components will be stored locally at InProduction’s facility in Goodyear, Arizona. Because much of the structure is custom-sized for the 16th hole, about 20% of the decks and beams will be redeployed to other events, while the remaining components will be reserved for annual assembly. Across InProduction’s broader inventory, those same modular systems will be reused across roughly 300 events each year, allowing materials to circulate continuously rather than being rebuilt from scratch. For InProduction, aligning with the tournament’s sustainability requirements was a core design constraint. As Ellis explains, the shift to a fully reusable structure was driven in part by a long-running effort to reduce material usage, particularly wood, scrim, and paint that previously had to be recycled, donated, or discarded after each event. From the outset, the goal was to cut construction-related material use. While the cassette flooring system required a higher upfront investment than traditional lumber, Ellis says it delivers long-term savings while eliminating painting and significantly reducing scrim usage, bringing the rebuild into closer alignment with the tournament’s zero-waste strategy. This is a different interpretation of temporary architecture: one that still appears overnight and disappears just as quickly, but behaves more like infrastructure than spectacle. In doing so, the 16th hole becomes less a one-off anomaly and more a case study in how large-scale events can rethink durability, waste, and experience. Designing for Experience The new structure firmly aligns with and reflects the Phoenix Open’s long-standing zero-waste ambitions. For Tara Hemmer, chief sustainability officer at WM, that significance of the redesign lies less in any single material choice than in how the structure fits into a broader closed-loop system. (Waste Management became the named sponsor of the Phoenix Open in 2010 and rebranded to WM in 2022.) “Reimagining the construction of the 16th hole and making it modular and completely reusable really speaks to the heart of what it means to be a zero-waste event,” Hemmer says. “This is just another step in that evolution.” The WM Phoenix Open officially became a zero-waste event in 2013, but Hemmer is quick to point out that it didn’t start with a playbook. “When we decided to try this, we had no idea how to get to a 100% zero-waste event,” she says. “So we had to try a lot of different things.” What emerged is a system designed across time, not just space. The process begins months before the tournament, immediately after the previous one ends. The minute the tournament ends, Hemmer and her team are already working on matters for the following year’s tournament. Aligning with vendors WM works directly with vendors, specifying which materials can and cannot be used. “We go to them and say, ‘These are the types of materials that you can and can’t use'” Hemmer explains. “Those are selected by the WM team, embedded by the WM team.” Vendors can propose alternatives, but only if those materials fit into the broader system. “Sometimes we take those and say, ‘That might be a best practice for all of our vendors,’” she says. The goal is simple but demanding: How can each item that comes onto the course be reused, donated, or recycled. That lifecycle thinking extends into unexpected areas. “One example I’m really proud of on 16 is beverages,” Hemmer says. “There are a lot of cold beverages, kept cold by ice. Ice melts, and that water has to go somewhere.” Instead of discharging it, WM designed a reuse loop. “Several years ago, someone came up with the idea: Can we take that water as it’s melting and use it as gray water for our portable toilets?,” said Hemmer. “That’s a great example of design thinking that happens throughout the year. The WM Green Scene At the Phoenix Open, there are no trash bins—only compost and recycling. The success of that approach depends as much on psychology as infrastructure. “We have to make things exciting but also easy,” Hemmer says. “Especially on 16, which tends to be very crowded.” Signage, bin placement, and staff engagement are carefully designed to reduce contamination. But the ambition goes further. WM spends a lot of time in researching how fans take their messaging home, and apply it. The WM Green Scene, an interactive fan zone, functions as the tournament’s sustainability classroom. Staffed by WM employee volunteers, the space uses golf-themed games and hands-on demonstrations to teach fans how to identify recyclable and compostable materials. In past years, visitors chipped items resembling cans, bottles, and food waste into the correct bins. This year, the space will also feature a three-dimensional WM Phoenix Open logo that allows fans to recycle bottles and cans directly. Free hydration stations encourage reusable bottles, while the tournament’s 50/50 raffles tie sustainability engagement to charitable giving. “We’ve learned so much by watching how fans interact,” Hemmer says. “And yes, we’ve also learned how many beverage containers can be consumed in a short period of time.” Behavior-led system design “We’ve all seen those cup snakes [collection of stacked cups] going up the 16th hole,” Hemmer says. “That’s important because we need to think through what fans are going to do and how we get those materials back.” On the 16th hole, behavior is part of the system design. All cold beverages cups used on course are recyclable. WM anticipates misplacement, cup snakes, and even thrown cups, collecting materials from the course and manually sorting every bag to ensure proper processing. Why Sports Are the Perfect Test Lab Sporting events offer a rare advantage for experiments such as the modular system: controlled chaos. “These events are remote,” Ellis says. “They always need infrastructure built temporarily—on a racetrack or a golf course. The level of detail increases every year.” Hemmer agrees. “The Phoenix Open is a closed event across several hundred acres,” she says. “We can test things at the 16th hole that we test differently at the 12th hole and see what works.” The stakes are high, but so is the payoff. All of this depends on leadership willing to push past comfort zones. “The WM Phoenix Open is the WM Phoenix Open because we take chances,” Eisenberg says. “We do things that not just other golf tournaments, but most other events don’t do.” Min Woo LeeAkshay Bhatia Nearly a century of community commitment That confidence comes from trust that has been built over 90 years of community involvement. “We have faith that if we build something and say it’s going to be great, our fans will support us,” he says. The Thunderbirds’ rotating leadership structure reinforces that mindset. “There is no dictator sitting on the throne for 10 years,” Eisenberg says. “Everybody comes in with fresh ideas, each trying to make it better.” That culture extends beyond spectacle. Eisenberg points to accessibility improvements and the addition of a family care center as examples of design that’s easy to overlook but deeply intentional. “I hope they don’t feel any burden getting in and out,” he says of fan accessibility. “I hope it just runs in the background.” When asked what other tournaments would struggle to replicate, Eisenberg is blunt. “It’s hard to replicate the time we’ve invested,” he says. “We have 90 years of goodwill in our community.” But he also believes the responsibility is clear. “If we can do this at our size and scale, no event has an excuse.” This weekend, fans will pack into the 16th hole once again. They’ll cheer, boo, and raise their cups skyward. What they likely won’t notice is the modular decks beneath their feet, the materials already destined for reuse, or the systems designed months earlier to make the experience feel effortless. “I hope they walk away thinking it was the most incredible temporary structure they’ve ever been in,” Eisenberg says. “And the best sporting event they’ve ever attended.” View the full article

-

What the bedroom can teach the boardroom about healthy, thriving relationships

After more than two decades as a psychosexual therapist, I have learned to listen carefully for what people are not saying. When vulnerability is close to the surface, uncertainty shows up quickly. Am I doing this right? Do I belong here? What am I allowed to ask for, and what will it cost me if I do? At its core, psychosexual therapy is not really about sex. It is about how humans relate when the stakes are high, when power is present, and when much of what matters remains unspoken. It is about noticing how meaning is made in moments of vulnerability and choosing how to respond rather than react. What continues to surprise me is how familiar these same dynamics feel when I step into boardrooms, leadership teams, and global organizations as a social psychologist. The context changes. The language becomes more polished. But the relational patterns remain strikingly consistent. Over years of working across more than forty countries, I came to realize that my clinical work and my leadership work were asking the same essential question: how do humans make meaning together when the cues are subtle and the consequences matter? Our jobs are rarely just jobs anymore. Many of us are seeking purpose, belonging, and fulfillment beyond a financial transaction. This is where I often see a widening gap between traditionally informed organizations and leadership styles, and those that have evolved alongside shifting sociocultural norms. We talk a great deal about generational differences. What if instead we looked at work through a relational lens? I am often described as a relationship architect. My work is about helping people make sense of their relational spaces so they can direct their energy, attention, time, and resources to where they actually bear fruit. Through this lens, I have come to see that thriving relationships, whether in the bedroom or the boardroom, are built on the same six fundamental ingredients. 1. Respect Respect is often misunderstood as politeness, obedience, or walking on eggshells. In intimate relationships, respect looks like keeping the other person’s priorities in mind, honoring boundaries, including your own, and practicing what I call the platinum rule: not treating others how you want to be treated, but how they want to be treated. In professional life, respect shows up in much the same way. It is reflected in how leaders honor boundaries around time, attention, and capacity. It appears when managers understand that what motivates one team member may exhaust another. Cultures of respect are built through everyday actions, arriving on time, being fully present, and not being distracted by a phone call in the middle of a conversation. 2. Trust Trust, in both intimate and professional relationships, is built through reliable and consistent actions repeated over time. Trust allows people to relax, to be vulnerable enough so connections could form, and to take risks. This looks like doing what you say you will do, taking accountability when you cannot, and repairing when things go off course. It means saying yes only when you can follow through, and saying no early rather than offering a lingering maybe. At work, trust functions the same way. Teams trust leaders who show up predictably and communicate clearly. Trust erodes when expectations shift without explanation or when people feel they must stay guarded. In organizations, low trust quietly taxes performance. People spend more time managing risk and protecting themselves than doing their best work. Over time, this shows up in burnout and avoidable turnover. 3. Attraction Attraction is often reduced to chemistry, but in reality it is about reciprocity and choice. In intimate relationships, attraction grows when people feel wanted and when there is space to be seen and chosen again and again. Attraction can take many forms, intellectual, emotional, social, physical, or financial. In professional settings, attraction shows up as engagement. Why do people want to be in the room? Why do they choose to stay with an organization or lean into a project? Leaders often underestimate how much attraction shapes retention. When attraction is absent, organizations rely on incentives. When it is present, people stay because they feel drawn to the work, the purpose, and the people. 4. Loving behavior Loving behavior is not about romance. It is about how we make others feel. In intimate relationships, it includes making the other person feel seen, special, and given the benefit of the doubt. It often means responding with generosity rather than suspicion when something goes wrong. At work, loving behavior translates into psychological safety. It shows up when leaders assume positive intent, acknowledge effort, and recognize unique contributions. People are more willing to stretch and innovate when mistakes are met with curiosity rather than punishment and they think their contribution is unique and it matters. 5. Compassion Compassion is often confused with empathy, but they are not the same. Empathy is feeling with another. Compassion is staying present without making the other person’s experience about yourself. In intimate relationships, compassion allows partners to witness each other’s struggles without collapsing into them or turning away. In leadership, compassion means to be there for the other in a meaningful way. Leaders who can hold space for difficulty without over relating or becoming defensive are better able to guide teams through uncertainty and change. 6. Shared vision Finally, shared vision gives relationships direction. In intimate relationships, it helps couples navigate priorities, negotiate and compromise intentionally, and make sacrifices that feel meaningful rather than resentful. In organizations, shared vision determines where resources go, how decisions are made, and what success looks like. Without it, teams may work hard while pulling in different directions. With it, even difficult choices feel coherent and strategic rather than personal. The architecture of effective human systems What I have learned, sitting with couples and working with leaders across cultures, is that relationships do not thrive by accident. Across every context I have worked in, the relationships that truly thrive share these six foundations. They are not optional and they are not interchangeable. Respect, trust, attraction, loving behavior, compassion, and shared vision are the conditions that allow people to bring their full capacity into a shared space. When they are missing, no amount of strategy or incentive can make up for it. The bedroom and the boardroom are not as far apart as we like to think. Both are spaces where power, vulnerability, and belonging are negotiated. These are not soft skills. They are the architecture of effective human systems. At the end of the day, the way we do one relationship is the way we do them all. View the full article

- Today

-

Mandelson and the money that never sleeps

This is truly grim for Keir Starmer, raising questions about his ethics as well as his judgmentView the full article

-

Can 2026 finally be the year Black-owned businesses are covered for their accomplishments, not just DEI?

Over the past two years, a troubling trend has started to take shape in the media; for a large majority of journalists, DEI framing became the default for covering Black businesses. What should be stories about innovation, resilience, market disruption, and leadership have increasingly been flattened into a single, repetitive narrative: DEI. Not the company’s business model. Not the founder’s vision or entrepreneur journey. Not the problem being solved or the customers being served. Just DEI. And it’s often framed through the lens of rollbacks, political backlash, or cultural controversy. This didn’t begin overnight, but in recent years and especially amid the political climate shaped by the The President administration, it has accelerated to the point of absurdity. Today, if a business is Black-owned, media coverage almost reflexively treats it as a DEI case study rather than a company. The founder becomes a symbol, success becomes secondary, and the story becomes predictable before the first paragraph is even finished. One Narrative, Over and Over Again If you listen closely to news interviews from 2024 until now between reporters and Black founders, nine times out of ten a pattern quickly emerges. The questions sound eerily similar. “How are DEI rollbacks affecting your business?” “What does the current political climate mean for Black entrepreneurship?” “How do you feel about corporate pullbacks from diversity initiatives?” My company, Brennan Nevada Inc. New York City’s first and only Black-owned tech PR agency, has been able to witness this firsthand through my daily interactions and interviews with members of the media. I’ve prioritized spending more time and conducting the necessary due diligence that preps my clients on how to engage, navigate, or just not participate in the same DEI obsessed interview. With these interviews between journalists and Black founders, the most important questions often go unasked, like “What problem does this business solve?” Or “What makes it competitive? “How did the founder build it?” And “What lessons can other entrepreneurs learn from its success?” And when coverage does come out, it typically leads with the current administration’s DEI rollbacks, and less like profiles of thriving companies. The rhetoric reflects commentary on diversity politics, with the business itself serving as a backdrop rather than the subject. When Black-Owned Becomes a Category, Not a Credential The underlying issue is subtle but very damaging: Black-owned has become synonymous with DEI in media framing. That equation is flawed and needs to be reworked. A Black-owned business is not inherently a diversity initiative or a political statement. It is first and foremost a business built by someone who just so happens to be Black. That’s it. Yet most media coverage today increasingly suggests that Black success exists primarily within the context of diversity efforts, and worse, that it is somehow dependent on them. When DEI programs face scrutiny or rollbacks, Black businesses are often portrayed as collateral damage rather than as resilient enterprises capable of thriving on merit, strategy, and execution. This framing does a disservice not only to Black founders, but to readers and audiences as well. It robs them of real business insight and reinforces the idea that Black success must always be explained through an external lens. The media tends to shift its tone to what’s currently happening in the cultural moment, especially when towards Black businesses. Five years ago during George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter movement that happened around Juneteenth in 2020, the media positively highlighted a lot more Black businesses alongside brands that pushed for DEI to address systemic barriers. The Cost of Poor Storytelling This media obsession with DEI is getting old really fast. It reduces complex entrepreneurial journeys into political soundbites. And it quietly undermines the credibility of Black founders by implying that their success is inseparable from institutional support rather than personal vision and capability. I’m not saying this is being done on purpose, because even well-intentioned coverage can fall into this trap, and oftentimes does. When every story leads with race rather than results, representation becomes reductive instead of empowering. The irony is that truly compelling stories are being missed. There are Black founders building category-defining products, solving real-world problems, scaling companies, and creating jobs; stories that deserve the same depth and seriousness afforded to any other entrepreneur. But those stories require more work. They require curiosity beyond a headline. They require journalists to move past the easiest narrative available. What’s Next for Black Stories in 2026 As media organizations reassess their role in shaping public discourse, 2026 presents an opportunity for a long-overdue reset. What would it look like to cover Black businesses the same way we cover all businesses, by focusing on innovation, leadership, and success first? What if founders were allowed to be experts in their industries rather than spokespeople for diversity debates? What if success stories were told as success stories? None of this means ignoring race or pretending systemic inequities don’t exist. That’s not what I’m saying since that context absolutely matters. But it’s my belief that context should inform a story not consume it. A Black-owned business should not automatically trigger a DEI narrative. And Black entrepreneurship should not be treated as a subplot in a political storyline. If the media wants to tell better stories in 2026, it needs to start by asking Black founders better questions, and by remembering that Black businesses are not symbols. We are enterprises. We are innovations. And we deserve to be covered as such. View the full article

-

Starmer apologises to Epstein victims

Prime minister addresses appointment of Peter Mandelson as US ambassador amid furore over links to disgraced financierView the full article

-

Lady Gaga featured in Rocket, Redfin Super Bowl ad

Looking to build on last year's live sing-along, Lady Gaga will be performing the theme to Mister Rogers Neighborhood in a campaign from Rocket and Redfin. View the full article

-

Lenders anticipate more revenue, but split on hiring plans

More mortgage professionals told National Mortgage News they expect their companies to hire, or stand pat, rather than fire workers this year. View the full article

-

Calls to rethink FHFA credit changes grow with FOIA reveals

The documents that the Housing Policy Council obtained from FHFA show past debate over one newer score and concerns about a single report with redacted context. View the full article

-

No one knows how to do layoffs. The psychology secrets to doing it humanely

Laying people off takes its toll. “Going back 25 years plus ago, I can still remember every situation that I had to do it in,” says Robert Kovach, a work psychologist and former corporate executive. The experience sticks with you, he says. Because it’s not just about “operational stress: Have I filled out the forms? Made the calls?” It’s also filled with “moral stress,” he adds. “Even when the decision is necessary, it can feel like a violation of your own personal values.” People laying off their coworkers often feel a clash between their responsibility to their company and their responsibility to be a good person to the people they’re laying off—particularly because layoffs are about a company needing to downsize, not always about the individual employee’s poor performance. These feelings have been coming up a lot lately, with layoffs reaching a high in 2025, and 2026 already being off to a layoffs-filled start, with Amazon, Pinterest, UPS, Home Depot, Dow, and others announcing cuts so far. While getting laid off can of course be devastating, there’s a big emotional challenge for the people who must do the laying off, as well. “How do you [show] respect [for] someone when you know you’re about to mess up their life?” Kovach asks. Though you may get feedback from higher-ups that you shouldn’t feel bad for letting someone go because it’s “just business,” you know deep down, that it’s not. “It’s all very personal,” Kovach says. Fast Company spoke with several mental health experts about the psychological underpinnings of having to lay someone off at work: the anxiety leading up to the event, the language to use during the moment of truth, and the guilt-provoking aftermath. Maintaining composure throughout is key—but how do you? Like Kovach says: You’re about to mess up someone’s life. Prepare “Being the person who has to deliver the news can be deeply distressing,” says clinical psychologist Melanie McNally. “Psychologically, many people experience anxiety, guilt, and even a sense of grief.” Approach a layoff meeting with “a clear idea of how you want to handle it,” says Victor Lipman, a Psychology Today contributor who provides coaching on mindful management at work. This doesn’t necessarily mean having a script ready, as that can come off robotic or impersonal, but lay out some key talking points you need to hit during the conversation. These might stem from organizational obligations. “Consult with the appropriate powers that be,” says Lipman, whether that’s human resources or the company’s legal department. You may be obligated to make certain statements about severance or explain the reason for layoffs in a certain way. It’s worth making sure those points are covered not just to fulfill the duties to your organization, but also to add some predictability to an otherwise unpredictable situation. You may also want to turn to colleagues for moral support. “Preparing emotionally might involve talking with a trusted colleague or supervisor,” says McNally. HR and mental health providers might also be available at your company to help with layoff prep. Ultimately, to go into a layoff meeting prepared, “it’s important to acknowledge and validate your own feelings first,” says McNally. One way to do that, says Kovach, is to “name that this is going to be tough.” Don’t pretend that you’re a robot—accept the emotional component and choose to lean into the empathy that comes with it. Be direct Everyone knows that there is a wrong way to lay someone off. When former Google employee Vivek Gulati prepared for a meeting one morning in January 2023, he checked his email to find an announcement that the company would conduct 12,000 layoffs. (At least this email was sent on purpose—just last month, Amazon accidentally sent employees an email announcing a round of global layoffs, which they later confirmed would indeed take place.) The next email in Gulati’s inbox contained his personal layoff notice. In a story he wrote about this experience for Harvard Business Review, Gulati also shares how his manager learned about his layoff. “He had tried to enter an office building, and his badge didn’t work,” Gulati writes. “It was a rough way to find out.” This is why mental health experts recommend conducting layoffs in person. “Employees deserve personal communication,” says Lipman. Laying someone off face-to-face exhibits emotional maturity in a company’s leadership. For the person conducting the layoff, however, the temptation to do so at a distance is understandable. By using text or email, you won’t have to see the person break down; you won’t be faced with trying to comfort them in a situation where you can’t provide much assurance. Kovach compares these at-a-distance layoffs to the studies from the 1960s where participants were told they were tasked with administering electric shocks to people they couldn’t see in another room. It was much easier to knowingly cause someone harm when the administrator didn’t witness it. While you should be physically present to lay someone off, it’s best if no one else is. “Ideally, layoffs should be conducted in a private, neutral space, like your office or a quiet meeting room,” says McNally. Be clear and direct. McNally suggests avoiding euphemisms, which might “confuse or minimize the situation.” For instance, you might feel compelled to cushion the blow with something like, “We’re going through a rough time financially now at the company, but if things turn around, I’d love for you to get your job back.” That likely doesn’t represent a promise you can keep. “You want it to be an efficient meeting,” Lipman says, one that doesn’t heighten existing emotional distress or provide false hope. Zoom can constitute such a private, neutral space if it’s facilitating a one-on-one meeting. This work for layoffs when that’s the usual way you communicate with an employee, but if you’re both working at a physical office, it’s best to eschew video calls in this tense moment. (And of course, mass firings over Zoom never go well, yet continue to be part of many big firms’ MO for laying people off.) Also: don’t bash the company. You’re still management, Lipman says, and need to act professionally. Lipman suggests saying something like, “I’m sorry to see you go. I’ve enjoyed working with you, but this is just something that has to be done.” While Kovach acknowledges certain enterprises might offer scripts to ensure everyone losing their jobs get treated the same (for legal and/or policy reasons), it’s okay to massage that script into your own words for a personal touch. At the organizational level, companies should give transparency about why the layoffs are taking place: was a particular department underperforming? Did a new product fail to meet revenue goals? Companies can also offer mental health resources for employees conducting layoffs, whether that’s in-house or via referrals. Also, the timing of layoffs should be well thought out and diligently coordinated—no one should find out they’re jobless because their key card suddenly doesn’t work. Ready for reactions “Calmness can be contagious, as can agitation,” Lipman says. Bad reactions to getting laid off “run the gamut,” says Kovach. From tears to physical outbursts to even suicidal ideation, responses reflect the fact that losing a job is a massive, detrimental shakeup to someone’s life and well-being. “It can fuel what somebody already believes about themselves, so they can slip into a narrative of ‘I just wasn’t worth keeping,’” says social worker Yvonne Castañeda. This is why an explanation of “it’s not you; it’s the company” can be so important. When encountering emotions from employees like shock, anger, sadness, anxiety, or “even relief,” McNally suggests, the best practice is to “allow space for these emotions and don’t try to ‘fix’ them right away.” That’s because you won’t be able to. Instead, take the time to listen to the employee, and validate their feelings in that moment. Provide support resources where you can, either from within your company or an outside trusted job placement organization, and give concrete details about severance packages. You can also encourage those who’ve been laid off “to reach out to family, friends, or mental health professionals,” McNally says. Not everyone handles these emotions calmly, even if you exude calm while conducting the layoff. “People are very capable of making a scene in a layoff situation,” says Lipman. “You want to be sure you have some backup in case anything goes wrong”—security, if it comes to that. Then there’s dealing with your own guilt for having to lay off a coworker. Maybe this person’s also a friend—someone with whom you’ve shared successes and failures at work, and whose families you’ve maybe barbecued with on Sunday afternoons. “It’s normal to feel guilt, sadness, or even anger after laying someone off,” McNally says. Reflecting on what took place, either alone, with friends, or with a mental health professional, can help process these emotions, as can generally practicing self-care, like getting enough sleep and exercise. At the end of your day, “reassure yourself that this was something you had to do in the management role that you were in,” Lipman says. If you offered empathy and clarity during a layoff—then it’s better you conducted it, than someone who considered it “just business.” View the full article

-

This year’s Olympic torch was designed to disappear

An Olympic torch is a small, flaming time capsule. Since the start of the modern Games in 1936, the torch has been passed by thousands of runners in a relay that goes from Olympia, Greece to the host city’s stadium. It’s a feat of engineering, since it needs to be durable enough to resist wind and rain, while keeping the Olympic flame arrive. But torch designers also imbue them with symbolic meaning. The Berlin 1936 torch was engraved with the Nazi iconography of an eagle. The Sapporo 1972 torch was a thin, cylindrical combustion tube that was a marvel of Japanese engineering. The Rio 2016 torch featured rippling blue waves celebrating the country’s natural beauty. What kind of torch represents the world we now live in? Carlo Ratti, the Italian architect and designer tasked with creating the torch for the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics, pondered this question for a long time. Ratti’s work largely explores the future of cities, particularly as global warming looms. For him, the biggest issues of our time are climate change and political polarization. Three years ago, he began the process of making a torch that captured these big ideas. His torch is perhaps the most sustainable one we’ve seen. It is made of recycled materials and it is designed to be refilled, so it can be used up to 10 times. It is minimalist to a fault, meant to fade into the background so that the world focuses on the flame within it. The flame, he says, is a powerful symbol of our joint humanity. “At this time of deep polarization and divisions,” he says, “we tried to strip down most of the things from the torch and really let the fire speak.” Fire, after all, predates every nation that now passes it along. “It’s one of the first technologies of mankind,” Ratti notes—something ancient, sacred, and shared long before borders existed.” A Lineage of Torch Makers Before sketching a single form, Ratti traveled to Lausanne, Switzerland, where every Olympic torch is preserved at the Olympic Museum. Seeing them in person, rather than online, made the pattern unmistakable. “Everybody somehow tried to capture the moment of their time,” Ratti says. Each torch, he observed, follows the same basic logic: a burner at the core, wrapped in a designed shell meant to convey meaning. Like car design, he explains, the engine is hidden beneath an eye-catching exterior. “And then the second thing is capturing the moment—connecting with local motifs.” Early torches, beginning with the relay introduced at the Berlin 1936 Summer Olympics, leaned heavily on classical references. The London 1948 torch resembled a chalice, while the Rome 1960 torch was designed to look like a column. Toward the end of the 20th century designs were more sculptural and declarative, often mirroring national ambition. The 1992 Albertville torch, designed by Philippe Starck, was in the shape of an elegant curve and was meant to reflect French modernism. The 1994 Lillehammer torch had a distinct Viking aesthetic. In the 21st century, the emphasis shifted again to focus on technological innovation. The torch for Sydney 2000 famously combined fire and water. Beijing 2008 engineered its torch to survive the winds of Mount Everest. A Radical Shift Against that backdrop, Ratti’s instinct was to do something quietly radical: design the flame, not the torch. That idea led to an inversion of the usual process. Rather than starting with an expressive exterior, Ratti and his team began with the burner itself, shaping only the minimum structure needed to hold and protect it. The result is the lightest Olympic torch ever produced—small, slender, and almost an afterthought in the runner’s hand. “We just start from the inside,” Ratti says, “and we do the minimal shape around the burner.” The effect is intentional disappearance. In photographs, the torch nearly dissolves into its surroundings, reflecting sky, snow, or cityscape depending on where it’s carried. The runner and the flame take precedence; the object recedes. Ratti describes the earliest sketch as “a runner with a flame in her or his hand instead of the torch itself.” There are a few earlier torch designers who had similar instincts. Ratti points to the torches designed by Japanese industrial designer Sori Yanagi for Tokyo 1964 Summer Olympics and Sapporo 1972 Winter Olympics as key inspirations—both exercises in restraint. What has changed, he argues, is technology. Today, advances in aerodynamics, materials science, and fuel systems make it possible to minimize the object without compromising the flame. That same logic extends to sustainability. Milano Cortina’s torch is not only smaller but engineered to be refilled and made largely from recycled aluminum. For Ratti, this approach is part of his broader philosophy. He argues that any designer working today must consider the environmental impact of their work. This applies to his work as an architect, creating a floating plaza in the Amazon River where people can experience the impact of climate change to turning a former railyard in Italy into a logistics hub featuring a renewable energy plant. “The first step in order to adapt is to use less, to use less stuff,” he says. Looking back at Olympic history is bittersweet. Earlier generations didn’t have to focus as much on sustainability because the climate hadn’t yet been so damaged. But today, it is impossible to design a torch without thinking of its environmental impact. For Ratti, it was important to imbue the torch with a clear message because the passing of the torch is seen by millions—possibly billions—of viewers around the world. By designing a torch that fades into the background, Ratti is making the case that we should pull back on overconsumption and excess, and focus our energies instead how we can work together to keep thriving as a species. “Maybe humanity will lose interest in oversized ballrooms and gilded pastiche,” he says. View the full article

-

AI Overviews: What Are They & How to Optimize for Them

AI Overviews are AI-generated summaries that appear for some search queries in Google. View the full article

-

Syngenta prepares to revive plans for IPO in Hong Kong

Chinese-owned company previously scrapped plans for listing in ShanghaiView the full article

-

How to Choose the Best Prompts to Monitor Your AI Search Visibility

After all, conversing with AI is unlike how we would traditionally search, since requests can be far more detailed, or occur in the middle of longer conversations. AI responses are also less consistent than organic search results, with both brand…Read more ›View the full article

-

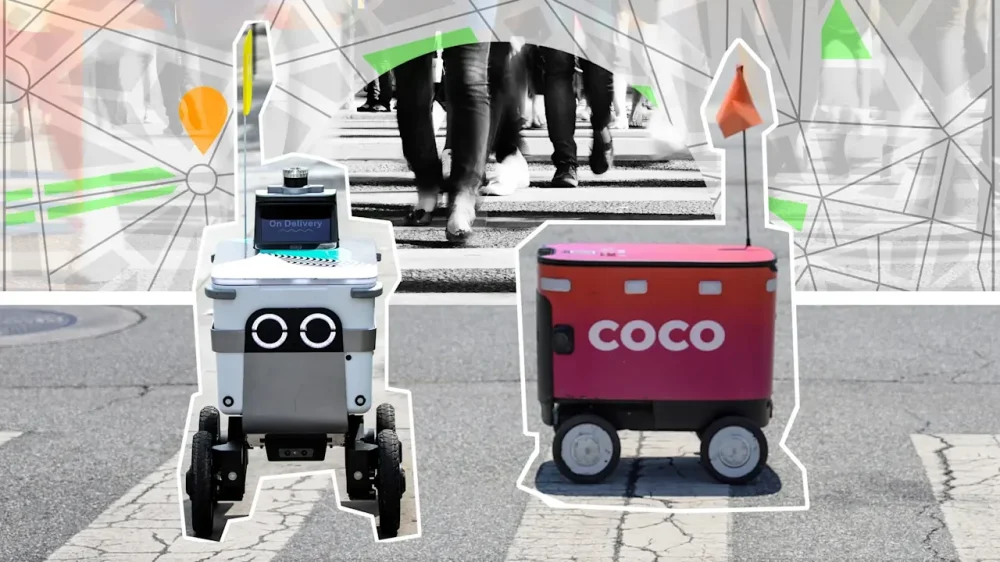

My neighborhood is pushing back against sidewalk delivery robots. The fight’s coming to your town next

It’s easy to be charmed by the first delivery robot you see. I was driving with my kids in our Chicago neighborhood when I spotted one out the window last year. It was a cheerful pink color, with an orange flag fluttering at about eye level and four black-and-white wheels. It looked almost like an overgrown toy. When I told the kids that it was labeled “Coco,” they started waving and giggling as it crossed the street. Over the months that followed, spotting Cocos rolling down the sidewalk became one of our favorite games. Then, last fall, another type of delivery robot appeared. This one was green and white, with hardier all-terrain wheels and slow-blinking LED eyes. My kids and I tried to read the name printed on its side as it idled across the street: Peggy? Polly? I later learned that the green newcomer was a Coco competitor made by a company called Serve Robotics. Every Serve robot is christened with its own individual moniker. At first, my interactions with the robots were mostly polite. One slowed to a stop while my dog cocked his head and sniffed curiously. Another waited patiently while we crossed Lincoln Avenue on our daily walk home from school, giving my stroller right of way on the ramp at the curb. In principle, they seemed like an improvement over double-parked delivery drivers and careening e-bikes. But some of my neighbors were having more negative experiences. Josh Robertson, who lives around the corner from me with his wife and two young children, was unnerved enough by a standoff with a robot that he decided to start a petition: “No Sidewalk Bots.” Thus far, more than 3,300 people have signed, with nearly one-third of those submitting an incident report. Through the incident field, Robertson has heard about feet being run over—a Serve robot weighs 220 pounds and can carry 15 gallons—near-collisions, unwelcome noise, blocked entryways, and more. In one case, a man required stitches around his eye after stumbling into a robot’s visibility flag. “Sidewalks are for people,” Robertson says. “Vehicles, in general, should be in the streets.” Robertson’s petition, the first so far in the cities where Coco and Serve operate, has revealed a groundswell of frustration over the strategically cute autonomous vehicles. In conversations with the CEOs of Coco and Serve, I got a close-up look at the arguments in favor of delivery robots, which the companies say are better suited to short-distance deliveries than 2-ton cars. If they have their way, what’s happening where I live will soon be playing out across dozens of cities as these well-capitalized startups seek to deploy thousands of their sidewalk bots. But in a matter of months, my neighborhood’s robots have arguably gone from novelty to nuisance. Silicon Valley startups are good at launching bright ideas, but bad at estimating their collateral damage. Are our sidewalks destined to be their next victim? From cute to concern In early December, around the same time the petition started to get local media coverage and gain momentum, I found myself sympathizing for the first time with the petitioners’ point of view. I was running an errand on a sidewalk that was crusted on one side with a thick layer of dirty snow when I noticed a Serve robot named Shima inching forward in my direction. It stopped as I approached, per Serve’s protocols. But in order to pass it by without stepping onto the snow, I had to navigate an inches-wide lane of space. If I had been pushing a wagon or a stroller, I wouldn’t have fit. The tree-lined sidewalks in my neighborhood are among the reasons I love living here. Outside my front door, near DePaul University, there is a constant stream of activity: bedraggled undergrads, eager dogs, bundled babies, dedicated runners. Within a 10-minute walking radius, I can find coffee, ice cream, playgrounds, vintage shopping, two Michelin-starred restaurants, my doctor, and my dentist. I began to worry that delivery robots would change Lincoln Park’s sidewalks for the worse. Why delivery robots are suddenly everywhere In the U.S., startups have been experimenting with delivery robots for close to a decade. Perhaps not surprisingly, some of the first were deployed in San Francisco. By 2017, the Bay Area city had become a hotbed for robot innovation—and residents’ frustration. In December of that year, city lawmakers passed an unusually restrictive policy limiting companies to deploying just three robots and requiring that a human chaperone accompany them. But the idea of sidewalk-based robots remained attractive to both entrepreneurs and delivery companies. Zach Rash and Brad Squicciarini founded Coco in 2020; as UCLA undergrads, they had built research robots to assess transportation and accessibility issues on campus. The following year, Uber spun Serve Robotics out of Postmates (which it had acquired for $2.65 billion to bolster its Uber Eats business), installing Ali Kashani, who had led Postmates X, as CEO. The delivery economy is booming, with three in four restaurant orders now eaten outside of the restaurant itself. For eateries and the platforms that enable their deliveries, robots offer a way around the labor costs and unpredictability associated with drivers. In an investor presentation from last year, Serve projected that its cost of delivery, with increased scale and autonomy, could be just $1 per trip. Mass adoption of delivery robots is now possible because of recent technology advancements, says Rash, Coco’s CEO, as he ticks off the list. “We have Nvidia compute on the vehicles that’s designed for robotics. Battery capacity has gotten a lot better, so you can drive multiple days without needing to recharge. Then, we have really robust supply chains around wheels, motors, motor controllers—a lot of the basic stuff you need to drive these things.” Put it all together, and Coco aims to operate a global fleet of 10,000-plus vehicles in select U.S. cities and overseas locations like Helsinki. “We’re delivering hot food, so [the robot] has to be able to get from point A to point B incredibly reliably every single time while maintaining a really low cost,” Rash says. Though Coco, like Serve, is only as wide as the shoulder width of an average adult, it can tote four grocery bags or even eight large pizzas. “It can fit all the types of things people need delivered,” says Rash, “but it’s incredibly compact, it’s safe, it’s energy efficient, and I think it’s the best way to shuttle stuff around our cities.” For now, that stuff consists almost entirely of restaurant deliveries. Both Coco and Serve have partnerships with Uber Eats and DoorDash. But the vision for the two startups extends far beyond burgers and burritos. “Someday our kids are going to look back and think how weird it was that a person had to be attached to every package that comes to our front door every day,” says Serve’s Kashani, who believes delivery robots’ true transformative potential lies in last-mile delivery. “I ordered a pair of climbing shoes for my daughter, and it was the wrong size,” he says. “It took two days to come, and then I had to deal with the reverse logistics of shipping it back and waiting for the next pair. Well, instead of ordering from Amazon, I could have ordered from a local store. [A delivery robot] could have shown up with two, three sizes. The robot could have waited while we tried the shoes and taken back the ones that didn’t fit. So you have all these new types of things that people can do that weren’t possible before because last-mile was just too inefficient and expensive.” Serve started 2025 with roughly 100 robots. By December, it had built 2,000. “That’s a point where it makes sense for the Walmarts of the world to want to integrate because now there’s a fleet they can access,” Kashani says, noting that Serve’s robots can accommodate more than 80% of Walmart’s SKUs. How Coco and Serve approach safety Coco and Serve, along with competitors like Starship (which raised a $50 million Series C last October and announced at the time it planned to have 12,000 robots by 2027), are all, in a sense, bets on autonomy. Behind the scenes, human operators are training the robots and stepping in to resolve problems. But the success of the model ultimately hinges on how well the vehicles learn to navigate neighborhoods on their own. Robot companies often point out that unlike self-driving cars, bots can usually just hit the brakes to de-escalate an encounter or avoid a collision. “It’s usually appropriate to stop, right? A car can’t just stop; you might cause an accident,” says Rash, acknowledging, though, that the sidewalk is a “much less structured environment” with “a lot more chaos.” “If my robot stops in the middle of a sidewalk, nothing bad happens,” echoes Kashani, adding that Serve robots have thousands of times less kinetic energy than a car. “That also gives us some affordances. Because we are moving more slowly, we have more time to think. So we don’t need as expensive of sensors, for example, or as many computers to achieve the same thing [as a self-driving car].” But despite those advantages, combined with years of training data, robots are still making mistakes. Social media abounds with robot bloopers—and worse. In one recent example, a high-speed passenger train in Miami mowed down a delivery robot stopped at a crossing on the tracks. Stopping, in that case, was fatal to the robot. In my own experience, one of the challenges pedestrians encounter with robots is simply their unpredictability. Coco’s robots tend to drive more smoothly, perhaps a result of the startup’s choice to have human pilots more involved. “Coco has been operating in Chicago for over a year with strong community support and without any major incidents or safety concerns,” Rash says. “Safety and community partnership are our top priorities.” Serve’s robots, in contrast, are more reliant on lidar and AI; their stilted driving often reminds me of the remote-controlled toy car my son used to drive as a toddler. A Serve spokesperson tells Fast Company: “We are working closely with city officials and local stakeholders to ensure responsible deployments, and we are committed to being a positive, safe, and respectful presence in the communities we serve.” Knowing that the robot is designed to cede to pedestrians is little comfort when it’s jerking back and forth right in front of you. What’s next for Chicago Robot deployment in Chicago is still, technically, part of a pilot program. Two city agencies, the Chicago Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection and the Chicago Department of Transportation, are jointly involved in licensing and assessment. If the City Council doesn’t renew the pilot, Coco and Serve’s licenses will expire in spring 2027. This week, one city alderman began soliciting feedback from his constituents as Coco and Serve seek to expand into other Chicago neighborhoods. Robertson, who created the anti-bots petition, is calling for an immediate halt to the program. The delivery robots’ promised benefits are appealing, he acknowledges, from reduced emissions to lower congestion. “But I think we should be skeptical [of those claims] and make sure we’re taking a data-driven approach,” he says. “What if robot trips replace bike trips instead of car trips? Or what if opening our sidewalks to these little vehicles leaves the total number of trips in the street unchanged? We need data. Then Chicagoans will be able to decide for ourselves if that’s how we want to tackle emissions and street congestion.” Robertson also raises the problem of enshittification, a term coined by author and journalist Cory Doctorow in 2022 to describe the perhaps inevitable degradation of online platforms over time as they seek to wring greater profits from their users. “Eventually, these robot companies, even if they do save consumers a buck or two right now on delivery fees, they’ve got to make a return for their investors, people like Sam Altman,” he says. (OpenAI cofounder and CEO Altman has invested in multiple rounds of Coco’s funding; last spring, OpenAI and Coco announced a partnership that will make use of Coco’s real-world data.) Already, ads supplement Serve’s revenue, turning some robots into rolling billboards and inserting the commercial into the public way. Last month in Chicago was bitterly cold and snowy, the kind of weather that drains robot batteries and presents obstacles to even all-terrain robot wheels. After growing accustomed to seeing Coco and Serve on a daily basis, I found myself wondering whether they were even attempting to brave the frigid January sidewalks. But I can’t say that I missed them. View the full article

-

There’s a new entry in the visual language of ICE raids: Purple vests

Federal immigration enforcement officers operating in New York will soon be met by legal observers in purple vests. New York Attorney General Letitia James announced on February 3 that her office is launching an initiative called the Legal Observation Project. Trained legal observers from her office—including lawyers and other state employees—will serve as “neutral witnesses” of the federal government’s immigration enforcement activity on the ground in the state, James’s office said. By observing and recording the actions of agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) or other federal agencies, which the public has a right to do, the observers will provide the attorney general’s office with information that could one day be used in future legal action if any laws are broken. By having a uniform, they are standing out and identifying themselves. “We have seen in Minnesota how quickly and tragically federal operations can escalate in the absence of transparency and accountability,” James said in a statement. “My office is launching the Legal Observation Project to examine federal enforcement activity in New York and whether it remains within the bounds of the law.” James’s office says specifically that observers from the initiative won’t interfere with enforcement activity and that their job is to merely document federal conduct safely and legally. Her office did not respond to a request for comment. The purple vests these observers wear will bear the insignia of the attorney general’s office. They’re the latest example of state-level officials turning to colored vests amid President Donald The President’s escalation of federal immigration enforcement. In Minneapolis, the Minnesota National Guard last month began wearing yellow safety vests so people could tell them apart from federal agents. In the absence of a single dress code, mostly masked federal officers from multiple agencies have worn a range of clothing, from jeans to fatigues and tactical vests in the Minneapolis area. The yellow vests are bright signifiers “to distinguish our members from those of other agencies, due to similar uniforms being worn,” as Minnesota National Guard spokeswoman Army Major Andrea Tsuchiya put it. A safety vest signals that the wearer wants to stand out and actually be recognized. In New York, the vests’ color “will aid in the ability of the trained legal observers to stand out in a crowd of bystanders and federal agents,” University of Minnesota College of Design faculty lecturer Kathryn Reiley tells Fast Company. “The federal agents tend to wear uniforms that are black, navy blue, or army green. The purple vests will produce the intended result of making the trained legal observers identifiable as a separate group of government employees that are not federal agents.” The ramping up of New York’s Legal Observation Project comes as the The President administration is scaling down its enforcement efforts in Minnesota. On February 4, the administration said it’s withdrawing 700 officers immediately, about a 25% reduction. The reduction in force in Minnesota only came following public pressure made possible thanks to citizen footage that showed the reality on the ground in Minneapolis and galvanized the public against ICE. A 56% majority of U.S. adults have little or no confidence in the agency, according to the latest American Values Survey released this week by the nonpartisan research nonprofit Public Religion Research Institute, including 85% of Democrats, nearly two-thirds of independents, and more than one in five Republicans. View the full article

-

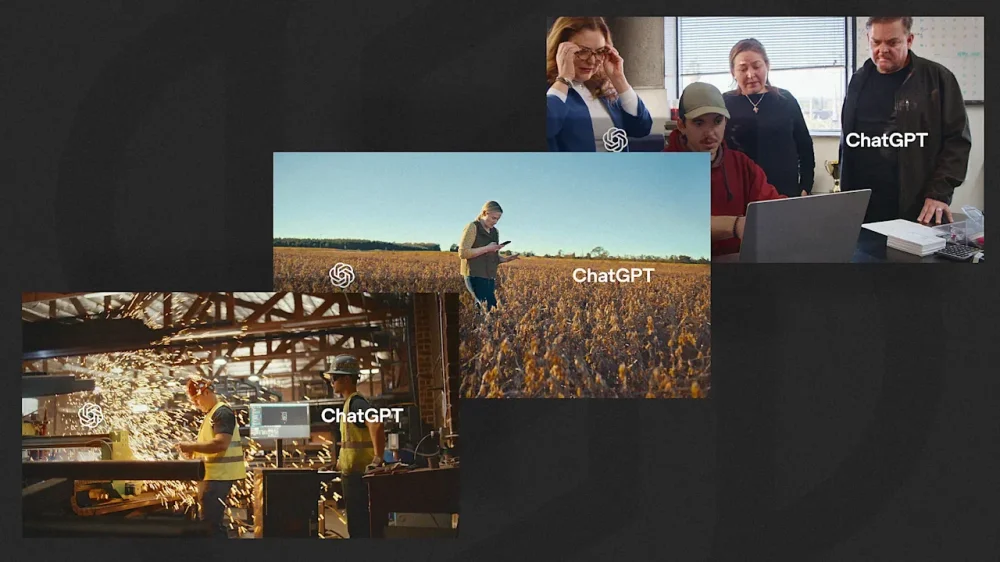

Exclusive: Inside OpenAI’s Super Bowl ad playbook

The news cycle is seemingly always full of OpenAI stories. The state of various investments from fellow tech giants like Nvidia and Microsoft, the competitive landscape between other big AI players like Google and Anthropic, and, of course, the more existential questions surrounding the direction of artificial intelligence and its impacts on society. For its new Super Bowl campaign, OpenAI is focusing on a simpler narrative: how ChatGPT helps people build things that have real-world impact. The company will roll out a 60-second national spot during the big game, but it has also made three regional ads, which are debuting exclusively on Fast Company. The regional spots (with both 30-second and long-form versions) profile three different American small businesses—a seed farm, a metal salvage yard, and a family-run tamale shop—that are utilizing ChatGPT to grow and thrive. According to OpenAI CMO Kate Rouch, more than half of ChatGPT users in the U.S. say it has helped them do something they previously thought was impossible. The company’s Super Bowl strategy aims to tell those stories. “Our core brand belief is that free access to these tools unlocks possibilities for people, and that anyone can build,” Rouch says. “We are for that person with an idea that doesn’t know how to make their idea real. Now they can, and that’s so much more important to us than any other thing we could use the Super Bowl for.” ChatGPT Stories For Rouch, these ads are personal. In fact, the guy who runs the salvage yard in one spot is actually her neighbor. “That’s how this series started,” she says. “He was showing me how he was using [ChatGPT]. That’s real. That’s cool. So the truth of this is how people are using the product.” The creative approach here is essentially a small-business extension of the vibe the brand unveiled back in September, showing individuals using ChatGPT for everyday things like finding recipes, sourcing exercise tips, and planning a road trip. It’s not the first time Rouch has used hyper-specific personal stories to illustrate the power of technology. When she was CMO at Coinbase, the brand used a similar approach to show that the crypto exchange and payments platform is a utility for everyday people, and a safe, dependable, and sensible option for modern commerce far away from Silicon Valley or Wall Street. The opportunity for Coinbase was to “leverage its position to help give regular people a voice,” she told me at the time. “This is not crypto bros and Lambos.” OpenAI faces a similar challenge of convincing people its tools are for more than asking simple questions. These ads, Rouch says, are a way to platform the very real stuff people are building with the technology. “Millions of people are using ChaGPT every day to do meaningful things in their lives that extend their sense of what’s possible and help them in real ways: running businesses, caretaking for their children and parents’ health, exploring their own health,“ she says. “This is happening and it matters.” Thankfully, OpenAI takes its brand challenges seriously enough not to jump on the Super Bowl AI gimmick bandwagon (see Svedka Vodka’s big game fever dream), instead emphasizing how many human minds and hands went into creating this campaign. OpenAI needs to be telling more stories like these. For as much enthusiasm as there is around AI from brands, many people are currently feeling existential dread over the technology. The good news for a company like OpenAI is that it’s liberated from selling capital “T” transformation in its ad work. Now the onus is on them to make it more human. Check out the long-form versions of each ad below. View the full article

-

Gilts and sterling hit by Starmer leadership speculation

Investors worry about political turbulence amid backlash over PM’s decision to appoint Peter Mandelson US ambassadorView the full article

-

Every doomed prime minister has a moment — this is Starmer’s

This end phase of his leadership requires a crisis or resignation to tip things over the edge View the full article

-

Everything you always wanted to know about burnout (but were afraid to ask)