Everything posted by ResidentialBusiness

-

Fujifilm’s new camera has a ‘Gen Dial’ so Gen Z can get the perfect retro shot

Fujifilm’s newest camera model, the Instax Mini Evo Cinema, is a gadget that’s designed for the retro camera craze. The device is a vertically oriented instant camera that can take still images, videos (an Instax camera first), connect with your smartphone to turn its photos into physical prints, and capture images in a wide range of retro aesthetics. It’s debuting in North American markets in early February for $409.95. Fujifilm’s new model taps into a younger consumer base’s growing interest both in retro tech and film photography aesthetics—a trend that’s been driven, in large part, by platforms like TikTok. The Instax Mini Evo Cinema turns that niche into a clever feature called the “Gen Dial”: a literal dial that lets users toggle between decades to capture their perfect retro shot. How the “Gen Dial” works Almost everything about the Instax Mini Evo Cinema screams nostalgia, from its satisfying tactile buttons to its vertical orientation—and that’s by design. According to Fujifilm, the camera’s silhouette is inspired by the 1965 Fujica Single-8, an 8-millimeter camera initially introduced as an alternative to Kodak’s Super 8. While the Instax Mini Evo Cinema does come with a small LCD display, its main functions are controlled with a series of dials, buttons, and switches, which Fujifilm says are designed “to evoke the feel of winding film by hand, add to the analog charm, and expand the joy of shooting and printing.” The most innovative of these is undoubtedly the Gen Dial. While there are plenty of existing editing apps and filter presets to give a photo a certain vintage look in-post, this may be the first instant camera to actually brand in-camera filters by era. The dial is labeled in 10-year increments, from 1930 to 2020. To choose an effect, users can simply click to the era they’d like to replicate, then shoot and print. According to the company, selecting “1940” will result in a look inspired by the “vivid color expression of the three-color film processes,” for example; 1980 pulls cues from 35-millimeter color negative film; and 2010 evokes the style of early smartphone photo-editing apps (throwback!). “Overall, our goal with Mini Evo Cinema is to deepen options for creative expression,” says Ashley Reeder Morgan, VP of consumer products for Fujifilm’s North America division. “Beyond video, the Gen Dial provides an experience to transcend time and space over 100 years (10 eras), applying both visual and audio to the mini Evo Cinema output.” For amateur photographers looking to achieve a certain vintage aesthetic without spending endless hours in Adobe Lightroom or fiddling with complicated camera settings, it’s the perfect intuitive solution. Retro cameras get a TikTok-driven boost For Fujifilm, the Instax Mini Evo Cinema is part of a broader, internet-driven revival of the brand’s camera division. While Fujifilm previously spent years moving away from its legacy camera business to focus on healthcare, its $1,599 retro-themed X100V camera—which went viral on TikTok—recently triggered a resurgence in its sales. The company’s most recent financials, released in September, show that its imaging division (which includes cameras) experienced a 15.6% revenue increase year over year, which Morgan says is attributable to the success of its instant and digital cameras. “Overall, we have been thrilled to see younger generations rediscovering the joy of photography, whether instant, analog, or digital,” Morgan says. The X100V’s popularity online is likely driven by Gen Z and Gen Alpha’s interest in retro tech aesthetics (see: Urban Outfitter’s iPod revival), as well as a more general resurgence in film photography in recent years. Analog cameras are having a moment, and companies like Polaroid and Fujifilm are cashing in. View the full article

-

AI hyperscalers need to restore trust—here’s how

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the market for artificial intelligence and its associated industries are over inflated. In 2025, just five hyperscalers—Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, and Oracle—accounted for a capital investment of $399 billion, which will rise to over $600 billion annually in coming years. For the first nine months of last year, real GDP growth rate in the U.S. was 2.1%, but would have been 1.5% without the contribution of AI investment. This dependence is dangerous. A recent note by Deutsche Bank questioned whether this boon might in fact be a bubble, noting the historically unprecedented concentration of the industry, which now accounts for around 35% of total U.S. market capitalization, with the top 10 U.S. companies making up more than 20% of the global equity market value. For such an investment to yield no benefit would be a failure of unprecedented proportions. In their book Power and Progress, Nobel Prize-winning economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson narrate the calamitous failure of the French Panama Canal project in the late 19th century. Thousands of investors, large and small, lost their fortunes, and 20,000 people who worked on the project died for no benefit. The problem, Acemoglu and Simon write, was that the vision for progress did not include everyone—and failure to incorporate feedback from others resulted in poor quality decision making. As they observe, ”what you do with technology depends on the direction of progress you are trying to chart and what you regard as an acceptable cost.“ Fast forward 150 years and a significant chunk of the U.S. economy is similarly dependent on a small coterie of grand visionaries, ambitious investors, and techno-optimists. Their capacity to ignore their critics and sideline those forced to bear the costs of their mission risks catastrophic consequences. Trustworthy AI systems cannot be conjured by marketing magic. We must ensure those building, deploying, and working with these systems can have a say in how we direct the progress of this technology. Mistrust and a general lack of optimism The data suggests that there is an urgent need to chart a new course. Even a generous analysis of the market for generative AI products would likely struggle to show how a decent return on the gargantuan investment in capital is realistic. A recent report from MIT found that notwithstanding $30 billion to $40 billion in enterprise investment into GenAI, 95% of organizations are getting zero return. It is difficult to imagine another industry raising so much capital despite producing so little to show for it. But this appears to be Sam Altman’s true superpower, as Brian Merchant has documented extensively. This is coupled with significant levels of mistrust and a general lack of optimism from everyday people about the potential of this technology. In the most comprehensive global survey of 48,000 people across 47 countries, KPMG found that 54% of respondents are wary about trusting AI. They also want more regulation: 70% of respondents said regulation is necessary, but only 43% believe current laws are adequate. The report concludes that the most promising pathway towards improving trust in AI was through strengthening safeguards, regulation, and laws to promote safe AI use. This, most obviously, sits in stark contrast with the position of the The President administration, which has repeatedly framed regulation of the industry as an impediment to innovation. But the trust deficit cannot simply be hyped out of existence. It represents a significant structural barrier to the take up and valuable deployment of emerging technologies. One of the key conclusions of the MIT report is that the small subset of companies that actually saw productivity gains from generative AI products were doing so because ”they build adaptive, embedded systems that learn from feedback.” Highly centralized decisions about procurement were more likely to result in employees being required to use off-the-shelf products unsuited to the enterprise environment and generating outputs that employees mistrusted, especially for higher-stakes tasks, resulting in work arounds or dwindling rates of usage. The problem is that these tools fail to learn and adapt. In turn, there are too few opportunities for executives to receive that feedback or incorporate it meaningfully into model development and adaptation. The narrative spun by politicians and media commentators that the AI industry is full of visionary leaders inadvertently points to a key cause of why these products are failing. Trust in AI systems can only be earned if feedback is both sought and acted on—which is a significant challenge for the hyperscalers, because their foundational models are less capable of adapting and responding to unique and varied contexts. Unless we decentralize the development and governance of this, the benefits may remain elusive. The workers’ view There are useful ideas lying around that could help navigate a different path of technological progress. The Human Technology Institute at the University of Technology Sydney published research about how workers are treated as invisible bystanders in the roll out of AI systems. Through deep, qualitative consultations with nurses, retail workers, and public servants to solicit feedback about automated systems and their impact on their work. Rather than exhibiting backward or unhelpful attitudes to AI, workers expressed nuanced and constructive contributions to the impact on their workplaces. Retail workers, for example, talked about the difficulties of automated systems that disempowered workers, and curtailed their discretion: “unlike a production line, retail is an unpredictable environment. You have these things called customers that get in the way of a nice steady flow.” A nurse noted how “the increasing roll-out of automated systems and alerts causes severe alarm fatigue among nurses. When an (AI system) alarm goes off, we tend to ignore or not take it seriously. Or immediately override to stop the alarm.” One might think that increased investment in such systems would contend with the problem of alarm fatigue. But without worker input, it’s easy to miss this as a problem entirely. The upshot is that, as one public servant put it, in workplaces where channels for worker feedback are absent, a necessary quality of employees was “the gift of the workaround.” Traditionally, this kind of consultation and engagement would happen through worker organizations. But with the rate of unionization slipping below 10% in the U.S., this becomes a problem not just for workers but also employers, who are left with few methods to meaningfully engage with their workforce at scale. Some unions are nonetheless leading on this issue, and in the absence of political leadership, might be the best hope of making change. The AFL-CIO has developed a promising model law aimed at protecting workers from harmful AI systems. The proposal focuses on limiting the use of worker data to train models, as well as introducing friction into the automation of significant decisions, such as hiring and firing. It also emphasizes giving workers the right to refuse to follow directives from AI systems—essentially, building in feedback loops for when automation goes wrong. The right to refuse is an essential failsafe that can also cultivate a culture of critical engagement with technology, and serve as a foundation for trust. Businesses are welcome to ignore workers’ views, but workers may end up making themselves heard in other ways. Recent surveys indicate that 31% of employees admit to actively sabotaging their company’s AI strategy, and for younger workers, the rates are even higher. Even companies that fail to seek feedback from workers may still end up receiving it all the same. Our current course of technological progress relies on narrow understandings of expertise and places too much faith in small numbers of very large companies. We need to start listening to the people who are working with this technology on a daily basis to solve real world problems. This decentralization of power is a necessary step if we want technology that is both trustworthy and effective. View the full article

-

Japan’s Takaichi to call snap election

Prime minister hoping to consolidate grip on power by winning majority for ruling partyView the full article

-

Why it feels so good when a meeting gets canceled, according to science

You know the feeling: You’re replying to emails, navigating open tabs, responding to direct messages, when suddenly, it happens—your standing weekly 2 p.m. gets canceled abruptly. “Giving everyone 30 minutes back today,” the organizer says. A rush courses through your nervous system: You’re free. Nothing about this recurring meeting is particularly onerous or necessarily stressful. And yet, at this moment, you feel like a burden has been lifted. Maybe you even audibly sigh in relief. That sudden sense that all is right in the world has a psychological cause, Dr. Wilsa Charles Malveaux, a psychiatrist in Los Angeles, explains to Fast Company. A neutralized threat in the brain “Our body is responding to the release of stress,” Charles Malveaux says. Between jobs, families, social obligations, and more, many of us feel overextended. At work, in particular, it can feel as though there’s no option to say no to something, like having to attend a meeting. So when a meeting gets canceled, “It takes the responsibility of having—or wanting—to say no away,” which leads to that sense of relief, Charles Malveaux says, noting that biologically, “We’re getting a sense of ‘I can breathe again.’” We’re programmed to anticipate threats, primarily through the amygdala, the structure in our brain that senses and responds to fear. Once it activates your fight-or-flight system, the brain releases cortisol, which often “lingers after a threat so that we remember how to recognize it and respond for the future,” Charles Malveaux says. So, weekly catch-ups, as harmless and banal as they may be, could actually activate “an elevated sense of threat” tied to anxieties around “being on time, or having to show up and present a certain way in a meeting,” she adds. “When you no longer have that, you feel that release.” But the reason why a particular meeting may trigger someone’s internal threat system depends on the individual. An invitation for introspection Beyond the joy of suddenly having extra free time to plow through piled-up tasks or ditch work early, there may be additional insights you can glean about yourself when certain meetings get canceled. “It’s probably not all of our meetings” getting canceled that makes us experience an absolutely electric sense of newfound freedom,” Charles Malveaux says. “It’s probably just some of them.” If we’re really paying attention to what adds stress to our day-to-day work life, and what does not, it could lead to some helpful introspection. Maybe certain meetings make us feel pressure to perform, or maybe there’s a colleague in that weekly meeting who triggers us. We can use that kind of personal examination to gather information and potentially move more mindfully throughout our workday. Understanding what types of meetings push us into an emotionally heightened state can help us approach them with a better attitude. Or, in the right environment, we may be able to approach our employers with those concerns and insights—something that could shift the company’s culture across the board. It’s a two-way street: Employers need to be receptive to the idea that all-hands-on-deck-style meetings, for example, may not be the healthiest option for everyone. Long-standing gripes Meetings in general remain a contentious aspect of professional life. Data shows that many of them truly do waste time and drain workers to be less productive. As the workplace at large has been reexamined and reimagined in the post-pandemic era, redesigning meetings has become more of a topic of discourse. Sometimes a meeting can just be an email—and if removing it from workers’ calendars can lower stress levels, why not do it? Building a work culture that understands the difference between necessary and unnecessary meetings is a “top-down issue,” Charles Malveaux says. After all, there’s only so much most workers in an organization can do to control the problem. Employers and upper-level management should “really look at what is actually necessary for optimal function and performance of your organization, versus control, which is a way a lot of people erroneously use meetings,” she says. A reframe That may be easier said than done, and the fact of the matter is that a lot of us will still be sitting through meetings we’d rather avoid as part of being in the workforce. Dealing with the resulting stress is all about energy management, Charles Malveaux suggests. Energy management is a fairly individualized journey, and includes “keeping track of the things that drain us, versus those that fill us back up, and making sure we book time” for the latter, she says. If you’re consistently finding yourself immensely relieved every time a meeting gets canceled, it might be worth zooming out and making sure your energy is being refilled elsewhere in your life—and not just being depleted constantly at work. “Doing an hour or so of something we hate or don’t want to participate in is going to feel a lot different from an hour of something that invigorates us,” Charles Malveaux says, noting, “Making sure that we tune into those things that make us feel good and then schedule time for [them]” is key, and it takes intentionality on the individual’s part. Making space for breaks can help keep burnout at bay, whether it’s just five minutes of silence in your car or a walk in a nearby park. Sounds like the perfect way to spend the time gained from that canceled meeting. View the full article

-

Why Levi’s is teaching high schoolers how to mend their clothes

Amanda Lee McCarty, sustainability consultant and host of the Clotheshorse podcast, remembers fixing a tear on her Forever 21 shirt with a stapler—just long enough to get through the workday before tossing it out. In the early 2000s, when fast-fashion brands began flooding the market, clothing became so cheap that shoppers could endlessly refresh their wardrobes. The garments were poorly made and tore easily, but it hardly mattered. They were designed to be disposable, encouraging repeat purchases. “It didn’t seem worth the time and effort to repair the top,” she recalls. “And besides, I didn’t have any mending skills at the time.” McCarty isn’t alone. Starting in the early 1900s, schools trained students—mostly girls—in the art of sewing and mending clothes in home economics classes. Students learned how to operate sewing machines to create tidy hemlines and sew buttons by hand. But by the 1970s, partly due to the feminist critique that home economics classes reinforced traditional gender roles, these courses slowly began getting cut from public schools. There are now several generations of Americans with no sewing skills at all. In a recent study conducted by Levi’s, 41% of Gen Zers report having no basic repair knowledge, such as fixing a tear or sewing on a button—which is double the rate of older generations. This also coincided with clothes getting cheaper, thanks to a global supply chain and low-wage labor in developing countries. Suddenly, clothes were so inexpensive that even the poorest families could buy them instead of making them. Eventually, as McCarty illustrates, they were so cheap that there was no point in even mending them. Today, the average American throws away 81.5 pounds of clothing every year, resulting in 2,100 pounds of textile waste entering U.S. landfills every second. This transformation of the fashion industry has led directly to the environmental disaster we now find ourselves in: Manufacturing billions of clothes annually accelerates climate change, and discarded clothes now clog up landfills, deserts, and oceans. Levi’s believes that one step in tackling the crisis is to teach Gen Z how to mend. The denim brand, which generates upward of $6 billion a year, has partnered with Discovery Education to create a curriculum aligned with educational standards that teaches high schoolers how to sew a button, mend a hole or tear, and hem trousers. This curriculum, which launches today, is available for free and will be shared with teachers across the country who can incorporate it into a wide range of courses—from STEM to civics to social studies. “Needle-and-Thread Evangelism” The idea took hold during a poker night. Paul Dillinger, Levi’s head of global product innovation, noticed that a button had popped off a friend’s Oxford shirt. “Oliver said he didn’t have time to throw it away and put on a new shirt,” Dillinger recalls. “It was an illustration of everything that’s wrong with the current paradigm. And it could be fixed with a little needle-and-thread evangelism.” Dillinger, who trained as a fashion designer and is a skilled garment maker, spent 20 minutes teaching the group—men in their mid-twenties—how to sew the button back on. Since then, he’s made a habit of preaching the gospel of mending with everyone in his orbit, including his colleagues at Levi’s. One of them was Alexis Bechtol, Levi’s director of community affairs. She saw an opportunity for the company to scale that education beyond informal demos. Bechtol helped spearhead the Wear Longer program and the partnership with Discovery Education, which specializes in developing age-appropriate lesson plans aligned with state and federal standards. Levi’s and Discovery Education worked together to create a curriculum that teaches students the foundations of mending a garment by hand without a sewing machine. There are four lesson plans that are each designed to take up a single classroom period and are flexible enough to be incorporated into courses across disciplines. Kimberly Wright, an instructional design manager at Discovery Education who worked on the curriculum, says the lessons aren’t positioned as a revival of home economics. Instead, they’re framed as practical, transferable skills relevant to a wide range of careers. “We’re seeing a resurgence in skills-based learning,” Wright says. “Across the country, there’s a shift toward not just making students college-ready, but career-ready.” The initiative is funded through Levi’s social impact and community engagement budget rather than its marketing arm, although the curriculum will be branded with the Levi’s logo. Dillinger believes that it is valuable for Levi’s to be associated with mending, because it emphasizes that its products are designed to be durable and long-lasting. “Levi’s wants to be the most loved item in your closet, the thing you wear most often,” he says. “If we empower our customers to sustain this old friend in their closet, it creates brand affinity.” A Small Fix for a Larger Systemic Problem At its core, the curriculum aims to challenge Gen Z’s perception of clothing as disposable. In theory, mending keeps garments out of landfills. “It’s about extending the life cycle of your product so you don’t have to buy something new,” Bechtol says. Gen Z is coming of age in a world dominated by ultra-fast-fashion players like Shein, where clothes are cheaper than ever. Mending is no longer an economic necessity—and in some cases, it can cost more in time and money than a garment is worth. Levi’s is trying to reframe mending as something else: a creative act that allows wearers to personalize their clothes. Over time, Dillinger says that personal investment changes how people value what they own. “Once you’ve invested time and care into repairing a garment, it shifts the value equation,” he says. “It becomes more like a plant or a pet—something you’re responsible for sustaining.” There’s no doubt that mending is a crucial part of the sustainable fashion movement. McCarty, who once stapled her shirt, now repairs her clothing to extend its life. But she points out that the fashion industry’s bigger problem is flooding the market with cheap clothes and encouraging constant consumption. While individuals can buy less and wear clothes longer, she says brands must take responsibility for producing fewer, more durable products. “It’s sort of like putting a Band-Aid on a bleeding wound and calling it fixed, when there are larger issues to deal with,” she says. McCarty extends this critique to Levi’s itself. While some Levi’s products are durable, she notes that the company also produces large volumes of lower-end jeans for retailers like Target and Kohl’s. These garments are often made with synthetic fabrics that are harder to repair and won’t biodegrade. “Levi’s is selling far more volume in lower-end jeans than they do in premium,” she says. “Some of these products are just not repairable.” Still, McCarty believes the Wear Longer program could meaningfully educate Gen Z—not only about mending, but also about the broader consequences of overproduction. Dillinger agrees. “Once you become a participant in the life of the garment, it becomes harder to ignore the broader industrial reality of how clothes are made,” he says. “You’re not participating in a similar set of tasks to the people who made the clothes.” Ultimately, Dillinger sees mending as a form of empowerment. Teaching young people how to repair their clothes gives them agency—to extend what they own and to engage with fashion more critically. “The sooner we respect kids as emerging adults with agency, the sooner they can make more responsible decisions for themselves,” he says. View the full article

-

In the U.K., Reddit is king

Reddit is now the fourth most visited social media platform in the U.K., overtaking TikTok. The online discussion platform has seen immense growth over the past two years, reaching 88% more internet users in the U.K., thanks to a combination of shifting search algorithms and social media habits. Three in five Brits now encounter the site while online, according to Ofcom, up from a third in 2023. The U.K. now has the second largest user base behind the U.S., according to company records shared with the Guardian. Reddit has also witnessed a drastic demographic change over the same period. More than half of the platform’s users in the U.K. are now women and one-third are Gen Z women, many of whom turn to the platform for forums dedicated to skincare, beauty, and cosmetics. A change in Google’s search algorithms last year, prioritizing content sourced from discussion forums, is partly behind the platform’s growth. Reddit has since become the most-cited source for Google AI overviews, after inking deals with Google and OpenAI, placing the platform at the lucrative intersection of traditional search and AI discovery. That’s combined with the ways we search online evolving in recent years. Many internet users bypass Google altogether and instead seek out human-generated reviews and opinions on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, or Reddit. “Gen Z are very open to looking online for advice around these life stage moments, like leaving home and renting for the first time, which happens a little bit later for some of this generation,” Jen Wong, Reddit’s chief operating officer, told The Guardian. “It’s a very safe place to ask questions about balancing a cheque book, or how to pay for a wedding.” Rival platforms like YouTube and Facebook have become subsumed with AI-generated slop, and the percentage of Americans using X since Elon Musk took over has dropped drastically—since overtaken by Reddit—according to new findings from Pew Research. Here, Reddit stands out as one of the last remaining platforms that holds a semblance of the small community-run forums of the early internet. Users follow topics of interest rather than influencers. Everyone is anonymous rather than at the mercy of an algorithm. Rather than offering answers it thinks users want to hear, or serving an endless stream of spam, bots and slop, the human-centred discussion threads that remain at its core invite curiosity—the foundation the internet was built upon in the first place. View the full article

-

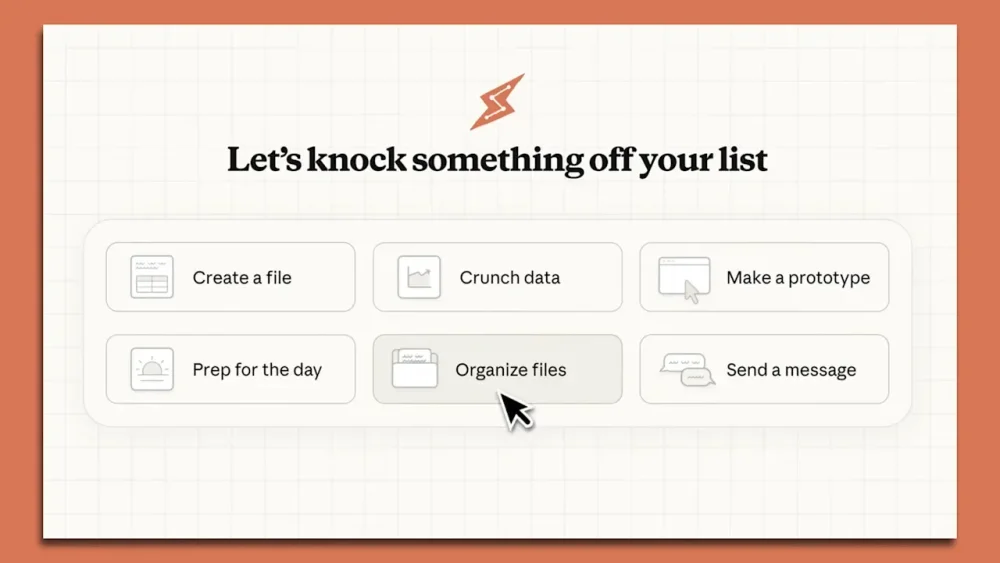

Why Anthropic’s new ‘Cowork’ could be the first really useful general-purpose AI agent

Anthropic’s Claude Code tool is having a moment: It’s recently become popular among software developers for its use of agents to write code, run tests, call tools, and multitask. In recent months the company has begun to stress that Claude Code isn’t just for developers, but can let other kinds of workers build websites, create presentations, and do research—and stories about non-coders completing interesting projects have filled social media. The latest offering, called Cowork, is a new version (and a rebranding) of Claude Code for work beyond coding, and it could dramatically widen the audience for Anthropic’s tools within the enterprise. Cowork is in “research preview” and is available only to Anthropic’s $100-per-month Max plan subscribers; there’s a waitlist for users on other plans. While Claude Code requires an API key and runs in the terminal, users can access Cowork through the Claude desktop app with a familiar chatbot interface. Most important, Cowork is built to access content stored in the file system on the user’s computer. A user can give the tool permission to modify, or just read, files in a given folder. They can also allow Claude to create new files or organize existing ones. The new tool could help Anthropic as it eyes an IPO in 2026 (reportedly at a $350 billion valuation), and may put additional pressure on Microsoft, which offers a number of predesigned AI agents (for things like research, analysis, and meeting facilitation) as part of its Copilot AI assistant. A December 2025 report from The Information claimed that Microsoft salespeople have been having trouble hitting their quotas selling the company’s Azure (cloud) AI products (including agents and agent builders) to enterprises. Microsoft denied the report. Cowork can do simple things like organize a user’s desktop folders or the contents of a “downloads” folder. Or it can search folders and emails for recent expenses and collect them in a new folder. But its most powerful use cases involve more complicated tasks. The tool can produce slide decks, large reports, or spreadsheets by calling up local (folder) data or data from connected business tools (such as Microsoft Teams or Zendesk) and then synthesizing the information. For multipart tasks, Cowork can create subagents for each part. Each of the subagents start with a clean context window so it has plenty of room to gather and remember information about its task. (In single chats with complex tasks, chatbots sometimes run out of context window memory, or become overwhelmed with data and then fail to make sense of it.) For example, a user might present the tool with a long document, then ask the AI to analyze it from different perspectives (legal, financial, ethical, public relations, etc.). A main agent might assign each perspective to a subagent. Each subagent would work independently to collect data and form a draft document, then return to sync up its work with that of the other subagents. A master document would be created and delivered to the user. Then the user might begin talking to the chatbot about how to refine the result. The Anthropic model that underpins Cowork is the same or very similar to the ones that power Claude Code. These models have already spent a significant amount of time working with real-world developers on real work. The models have already seen lots of different kinds of complex tasks, including unique edge cases, and have run into many types of roadblocks. They’ve been trained on lessons learned from that experience. For those reasons, along with the inherent quality of Anthropic’s models, workers may find in Cowork their first taste of AI agents that build trust through quality—which could change how people see the technology as a tool that can actually help them at work. View the full article

-

What Taoism can teach us about learning in the age of AI

As our attention spans and cognitive abilities are increasingly damaged by digital overuse and AI-mediated shortcuts, the ability to focus deeply and learn something in depth is quickly becoming a critical skill. Never have we had such broad access to information. And never have so many people felt unable to concentrate long enough to truly master anything. Learning is everywhere, yet depth feels elusive. In a world where artificial intelligence can retrieve, summarize, and recombine information faster than any human, what remains valuable is the capacity to incorporate it. And for that to be possible, you need to stay with a subject long enough for it to transform you. To develop judgment, sensibility, and embodied understanding. Engineering scarcity in a world of abundance It is striking that some of the wealthiest people on the planet are actively trying to recreate conditions of scarcity for learning. Silicon Valley billionaires famously send their children to schools with no screens. The goal is to give the young brains of their offspring the chance to build attention, memory, and imagination without constant digital solicitation. And to give them an edge over hyperconnected, cognitively eroded plebs. Conscious of the erosion of their cognitive abilities, more and more people attempt to engineer artificial information scarcity for themselves. They block websites, silence notifications, use distraction-free devices, or retreat into “deep work” bubbles. A growing number deliberately swap smartphones for so-called dumb phones, accepting inconvenience in exchange for cognitive space. Among younger generations, a curious trend has emerged on TikTok: videos of people filming themselves doing absolutely nothing. What looks like absurdity is, in fact, a rebellion against overstimulation—a desire to recover the ability to sit with oneself without external input. All these strategies point to the same intuition: Abundance without boundaries is not liberating. It is paralyzing. And learning, in particular, seems to require limits to flourish. Learning when the future is radically uncertain This matters all the more because learning has lost one of its traditional motivations: predictability. For decades, acquiring skills was tied to relatively stable professional trajectories. You learned accounting to become an accountant, law to become a lawyer, engineering to become an engineer. The link between effort and outcome was broadly intelligible. Today, nobody knows which skills will be valued among future white-collar workers—or whether many of those will still be hired at all. Entire professions are being reshaped, fragmented, or automated faster than educational institutions can adapt. In such a context, learning can feel strangely demotivating. Why invest years mastering something that may soon be obsolete? And yet, this very uncertainty may make deep learning even more meaningful. When external guarantees disappear, learning becomes less about employability and more about orientation, about building internal resources like discernment, aesthetic sense, and intellectual resilience. This is where Taoist-inspired approaches to learning suddenly feel increasingly relevant. What’s Taoism? As one of the great spiritual traditions of China, it is traditionally associated with the Tao Te Ching, attributed to Lao-Tzu (around the 6th century BCE), and later texts such as the writings of Zhuangzi. At its core lies the concept of the Tao—often translated as “the Way”—the underlying, ever-changing principle that governs the natural world. Taoism is not a doctrine of control or optimization. It emphasizes alignment rather than domination, and harmony rather than performance. One of its central ideas is wu wei, often mistranslated as “nonaction” but better understood as “effortless action”: acting in accordance with the natural flow of things rather than forcing outcomes. Another key idea is pu, the “uncarved block,” symbolizing simplicity, openness, and unconditioned potential. Taoist wisdom consistently warns against excess—of desire, of knowledge, of intervention—and values emptiness, slowness, and restraint as conditions for clarity. In short, Taoism offers a sharp lens through which to rethink how we learn today. A lesson from Fabienne Verdier: scarcity as a teacher I was reminded of this while reading Passenger of Silence, French artist Fabienne Verdier’s remarkable account of the 10 years she spent in China in the 1980s, studying calligraphy and immersing herself in Chinese artistic and philosophical traditions. (Until March 2026, some of her striking works are being exhibited at the Cité de l’Architecture museum in Paris, offering a visual echo to the intellectual journey she describes.) Verdier recounts the ascetic teaching methods of her calligraphy master. The caricature comes to mind immediately: the merciless master in Kill Bill, forcing Beatrix Kiddo to repeat the same gesture endlessly, withholding validation until the student is almost broken. Repeat and repeat and repeat the same stroke—until boredom, frustration, and despair surface. Wait months, sometimes years, before being deemed worthy of moving on. Prove motivation, patience, and humility before even being accepted as a student. At one point in her book, Verdier recounts a decisive moment of collapse after being asked to paint endlessly the same strokes—one that her master greets not with concern, but with joy. After months and months of training, I burst out one winter morning in front of my master: “I can’t go on anymore; I don’t know where I am. In short, I don’t understand anything anymore.” “Good, good.” “I don’t know where I’m going.” “Good, good.” “I don’t even know who I am anymore.” “Even better!” “I no longer know the difference between ‘me’ and ‘nothing.’” “Bravo!” The more I fumed, the more delighted he became, his face radiant with happiness and amazement. He was hopping with joy, tears in his eyes. I went on, overwhelmed by an inner pain, thinking he hadn’t understood what I was saying: “After all these years of practice, I realize that I am still just as ignorant in the face of the universe. I will never manage to accomplish what you are asking of me.” “Yes, that is exactly it,” he said, clapping his hands with joy. He danced in place with an incomprehensible delight. At that moment, I thought he was delirious. “You have no idea how much pleasure you’ve just given me! There are people for whom an entire lifetime is not enough to understand their own ignorance.” 5 Taoist principles of learning we could all adopt 1. Learning as transformation, not acquisition: In Taoism, knowledge is not something you accumulate but something you become. The Tao Te Ching repeatedly suggests that true understanding comes not from adding more, but from stripping away the superfluous. Mastery is not about collecting credentials or information, but about internal change. Learning is successful when it alters how you act in the world. 2. Patience as a prerequisite: Lao-Tzu famously writes: “I have just three things to teach: simplicity, patience, compassion. These three are your greatest treasures.” Patience is a condition for learning to occur at all. Progress can’t be forced. Growth unfolds in its own time, like the seasons. In learning, waiting is not wasted time but part of the process—especially when what is being learned is judgment, taste, or sensibility. 3. Scarcity and simplicity as cognitive discipline: Taoism consistently warns against excess. The ideal learner is not surrounded by infinite resources but protected from distraction. Fewer tools, fewer references, fewer stimuli allow attention to settle. As Lao-Tzu notes: “When you realize there is nothing lacking, the whole world belongs to you.” 4. Process over outcomes: Taoist wisdom is skeptical of linear progress and measurable outcomes. Learning does not move smoothly from beginner to expert; it circles, deepens, stalls, and restarts. This stands in stark contrast to modern learning cultures obsessed with efficiency, milestones, and KPIs. If you focus too much on results, you miss the internal transformations that constitute real mastery. 5. Boredom and not-knowing as thresholds: Perhaps the most radical principle is the role of boredom. Taoist practices value stillness and emptiness as gateways to insight. In learning, boredom is often the point where superficial motivation collapses—and where something deeper can begin. To tolerate boredom, uncertainty, and silence is to resist the constant stimulation of digital environments. Learning humility in an age of hubris Taoism dismantles the illusion of mastery and domination. It reminds us that knowledge is always partial, that control is fragile, and that force ultimately backfires. Water defeats rock. Those who claim to know do not truly know. Learning, in this tradition, is inseparable from the recognition of one’s ignorance. Verdier’s master does not celebrate her despair out of cruelty, but because she has finally reached a point where ego, certainty, and ambition collapse. Only then can real learning begin. This stands in sharp contrast with our contemporary climate of hubris—technological, economic, and political—where confidence is rewarded more than doubt. Taoist learning offers a counter-ethic. It teaches that in brutal times, restraint may be the most radical form of resistance. View the full article

-

What Google SERPs Will Reward in 2026 [Webinar] via @sejournal, @lorenbaker

The Changes, Features & Signals Driving Organic Traffic Next Year Google’s search results are evolving faster than most SEO strategies can adapt. AI Overviews are expanding into new keyword and intent types, AI Mode is reshaping how results are displayed, and ongoing experimentation with SERP layouts is changing how users interact with search altogether. For SEO leaders, the challenge is no longer keeping up with updates but understanding which changes actually impact organic traffic. Join Tom Capper, Senior Search Scientist at STAT Search Analytics, for a data-backed look at how Google SERPs are shifting in 2026 and where real organic […] The post What Google SERPs Will Reward in 2026 [Webinar] appeared first on Search Engine Journal. View the full article

-

Strong UK offshore wind auction boosts plan to decarbonise by 2030

Demand from developers beat analysts’ expectationsView the full article

-

BP warns of $4bn-$5bn impairment charge in energy transition business

UK oil major attributes charge to gas and low carbon energy unitView the full article

-

IMF presses governments to step up support for workers displaced by AI

Analysis finds evidence of the technology hitting wages and employment in certain areasView the full article

-

Your employees aren’t disengaged. They’re fed up

Quiet quitting. Silent space-out. Faux focus. Call it what you want, a lot of today’s workers are going through the motions on the surface while quietly powering down beneath it. Nearly half of Gen Z employees say they’re “coasting,” and overall U.S. employee engagement sits at a decade low. When engagement fades, performance becomes performative. But disengagement isn’t just a problem to solve, it’s a signal to heed. Employees aren’t turning off. They’re trying to tell us something. As CEO of SurveyMonkey, I’ve witnessed how curiosity can be the cure to the workplace phenomenon “resenteeism”—a state of resentment combined with absenteeism—which is often fueled by the current economic uncertainty, high-profile layoffs, and the always looming threat of a recession that compels employees to stay in difficult jobs. Here are a few best practices: When you ask better questions, you reveal truer truths By asking better questions, you can get to the heart of what employees really need. A few small shifts in your approach to asking can make a big difference. Ask about feelings and solutions separately. Instead of asking, “What do you think about manager-employee communications?” Ask, “How do you feel about manager-employee communications?” Then, separately, “What do you think would make it better?” Dividing feelings and solutions into two distinct categories enhances understanding of each, providing a better roadmap to real change. Keep it simple. Avoid double-barreled questions that blur answers. Instead of asking, “How satisfied are you with your manager’s communication and support?” Ask two clear questions: one about communication and one about support. Be receptive to harsh truths. When you ask questions with a genuine interest in the answers, employees will be more likely to open up, share ideas, and re-engage. Asking harder questions often reveals truer answers that get to the heart of the matter faster. You’ll hear frustrations, confusion, and even criticism. But discomfort is often where innovation starts. Plan to be uncomfortable, and you won’t be disappointed. Be clear about anonymity. Anonymity can surface more honest feedback, but it’s not always the best route. Sometimes you’ll want to follow up on a great idea or recognize the person who shared it. Either way, be transparent about whether feedback is anonymous. People will keep sharing when the ground rules are clear. Make every day listening second nature Too often, conventional check-ins like annual reviews and quarterly surveys feel like impersonal boxes to check. Approached clinically, managers are more likely to miss early signs of disengagement. When people feel like their feedback is lost in a dashboard, they stop providing it. Employees know when feedback requests are performative, and they respond as such. Sincere listening needs to be lighter, faster, and less formal. You can normalize curiosity in small, consistent ways, including: Ask a simple question at the end of a team meeting: “What’s standing in your way today?” or “What can we improve this week?” Run short, focused pulse surveys that take 60 seconds or less to answer. Follow up verbally when something needs clarification, rather than using email or Slack. Share one piece of feedback you’ve acted on recently. My team has seen that a five-minute feedback loop can reveal what a 50-question survey misses. It’s less about frequency and more about follow-through. When employees see their input lead to action, trust grows, and engagement follows. Take every comment seriously Even the tiniest morsel of feedback can spark outsized change. A lone remark can connect teams, bridge silos, and turn passive frustration into active progress. One of the best examples I’ve seen came from a deceptively simple comment in a benefits survey from our Chief People Officer’s team. While the overall feedback was positive, one person asked: What about the janitorial staff? This simple yet powerful question led her team to re-evaluate benefits for the vendor partners who keep our offices running every day. Within months, she expanded health insurance, paid time off, and transportation benefits to all contract employees. The ripple effect of this change was immediate. Our contractors said they felt more motivated, and regular employees were proud to work for a company that took care of everyone under its roof. That motivation and pride translated into stronger engagement, higher productivity, and a more unified culture. All of it started with a single comment, taken seriously. Start small, stay curious Resenteeism isn’t just a blip. It’s a signal. If we know how to listen, we can turn that signal into strategy. The key is to start small and stay consistently curious. Ask one question. If you don’t get specific feedback, such as a vague “All good!” or “It’s fine!”, reframe it: What part of this experience didn’t land for you? If it’s a 9 out of 10, what would make it a 10 out of 10? You can’t reverse disengagement overnight, but you can make incremental progress—and progress compounds. It’s a philosophy my team and I try to live by: better is better. What question will you ask today? View the full article

-

China blames US for trade imbalances as surplus hits record $1.2tn

Exports soar as world’s second-largest economy shakes off Donald The President’s tariff threatView the full article

-

NZ central bank chief rebuked over support for Fed’s Powell

Foreign minister warns newly appointed governor to ‘stay in her New Zealand lane’View the full article

-

Advertising group Dentsu’s push to sell global unit close to collapse

Potential buyers dropped out of talks to buy Japanese agency’s underperforming international armView the full article

-

5 Ways To Reduce CPL, Improve Conversion Rates & Capture More Demand In 2026 via @sejournal, @CallRail

Maximize your online ads with 5 expert PPC tips that will help you drive more traffic from and increase conversions across your ad sets. The post 5 Ways To Reduce CPL, Improve Conversion Rates & Capture More Demand In 2026 appeared first on Search Engine Journal. View the full article

-

Get in shape at home with these 4 free apps and sites

Another year, another fresh start. And if you’re like me, that fresh start often comes with the best intentions of getting into shape. But then reality hits: It’s January, it’s cold, and the idea of leaving the house to brave the gym (and all the other resolution people) is wholly unappealing. Fear not, fellow homebody. This year, we’re going to conquer those fitness goals from the comfort of our own living rooms. No gym fees, no icy commutes, no waiting in line for a treadmill. Seven (iOS/Android) For better or worse, if you have a phone and seven minutes, you no longer have an excuse. Seven is the heavy hitter in the “micro-workout” space. It focuses on high-intensity interval training (HIIT) circuits that require no equipment other than a chair and a wall. While the app has a subscription Club for extra variety, the classic Full Body circuit is free and stays true to the original scientific study that started the craze. It’s gamified, too, so you earn achievements and lose “lives” if you skip a day. Down Dog (iOS/Android/Web) For those looking to find their zen while building strength and flexibility, Down Dog is a revelation. While it offers premium subscriptions, the free version still provides a fantastic yoga experience. What sets it apart is its dynamic sequencing. Each time you start a practice, it generates a new flow, so you never get bored. You can customize the length, focus (like hip openers or sun salutations), and even the instructor’s voice. It’s like having a personal yoga teacher on demand. Nike Training Club (iOS/Android) If you get bored with the same workouts time and time again, then Nike Training Club is for you. This free (as in truly free) app is packed with hundreds of workouts, ranging from strength and endurance to yoga and mobility. You can filter by workout type, muscle group, equipment (or lack thereof), and even duration. Many of the workouts are led by Nike master trainers, providing excellent guidance and motivation. It puts a massive, high-quality fitness library at your fingertips. Darebee (Web) My personal favorite, Darebee is a non-profit, completely free resource chock full of thousands of visual workouts that you can print out or follow on your phone. It offers everything from ever-changing daily exercises to structured 30-day programs. It’s a community-run project that proves you don’t need a fancy subscription to get results. If you’re looking for a straightforward, easy to follow, self-paced workout hub, this should be your first stop. View the full article

-

our employee misses too much work, boss is different in person, and more

It’s five answers to five questions. Here we go… 1. Employee misses a ton of work and we don’t know what to do I manage the manager of a newer employee. We’re outside the U.S., where everyone has generous paid vacation and sick leave. The problem is that she takes long vacations at inconvenient times and far more sick days than average. Taken together, these absences are creating real strain on the team. Because some of it may be health-related, I’m not confident about how to address it. Since starting a year ago, she has taken far more (five times more) sick leave than her peers, often on Fridays or Mondays or on days with important deadlines and presentations. Her work gets done, but only because her colleagues scramble to cover for her. She points to meeting deadlines as proof of excellent performance, without acknowledging the team’s role in meeting those deadlines when she was not in. At least five times she has called out sick on the day of a major presentation, leaving others to step in. Yet in her annual goals she asked for more presentation opportunities, not demonstrating awareness that she has missed several. She also missed a pre-vacation handover meeting by calling out sick. My manager and my superior have both remarked that they suspect some of her sick days may be chosen to extend vacations or recover from late nights out, which has made this a reputation issue as well. We have tried to be supportive. Conversations have asked what we can do to help, whether she needs accommodations, or whether she is receiving adequate medical care. She insists she just gets sick a lot. Once she mentioned she may have a serious condition, but she has not followed up with a doctor. Vacations have also caused disruption. Twice she has claimed her partner booked surprise trips without consulting her, presenting them as non-negotiable. Even if she didn’t plan the trips herself, the timing still disrupted the team and required coverage. We approved the time off but stressed that she remains accountable for deadlines and handovers. Her metrics look fine only because others are compensating. She doesn’t show urgency when she does return, and her new manager, who is task-focused, is already struggling with her lack of accountability. How do I balance compassion for her situation with the need for accountability and reliability on the team? The lowest hanging fruit here are the surprise trips. You probably felt backed into a corner and like you had to approve those because of the way she presented them, but actually you could have said, “Unfortunately, no, we can’t approve that time off. You’ve been out a lot recently and have deadlines during that time and we need you here to cover XYZ.” It’s nice to accommodate this kind of thing when you can, but when someone is already struggling with not being at work enough, you can set limits and say no. Beyond that, if she’s not there frequently enough to get her work done at the level you need or if the burden of covering for her is falling unfairly on coworkers, you can address that too. You didn’t say whether she’s using more than her allotted sick leave but if she is, you can say, “We can accommodate the X days of sick leave per year that’s part of your benefits package, but beyond that we need to be able to count on you to reliably be here.” What the sentence after that should sound like depends on the specific laws in your country, but in the U.S. it would be something like, “If there’s a medical issue in play, we can start a discussion about accommodations and see how to make this work, but otherwise we really do need you to be here reliably.” It would also look like holding her to meeting deadlines and other metrics, and holding her accountable when she doesn’t and when others have to cover for her — to the point of considering whether or not she can do the job you need done, because right now it sounds like she’s not. Since you manage her manager, you likely need to coach her manager through all of this; what she’s doing now isn’t working. Related: how to deal with an employee who takes too much sick leave 2. Why is my boss so different in person? I’ve been at my current job for three years, and I still can’t figure out why my boss’s personality changes so drastically when in-person compared to on the phone or in virtual meetings. He is stationed at a different office than me. If we’re talking on the phone or in a virtual meeting, he is very chatty and will laugh and make jokes. When we are in person, however, he becomes very short-tempered, does not laugh, and can be somewhat condescending. Why would anyone change so much when face-to-face? Good question! It’s obviously hard to say with any certainty, but I can think of a few possibilities. He could be socially anxious and when he’s in person it comes out by seeming cold and distant. Or he could be kind of a jerk and can hide it better when he’s not face-to-face. Or — I’m completely spitballing now — when he’s in his own office, he could share space with someone he wants to make a good impression on, but he feels no such compunction when that person isn’t around. Or the opposite also could be true; there could be someone in your office who sets him on edge and so he’s crankier when he’s there. Or hell, maybe the commute puts him in a bad mood, or they just have better coffee at the other office. It’s a weird pattern, though. 3. Can we discuss personality when evaluating job candidates? I understand that academia is its own beast in terms of job searches and procedures, but I’ve been running into a frustrating issue when my department discusses job candidates. Our job search procedures involve Zoom interviews, and then invitations to day-long campus visits. In the last few years, various department members have requested that we avoid discussing “personality” attributes and focus simply on their qualifications. On the one hand, I understand where they’re coming from as we know this could potentially work against neurodivergent individuals, and there’s a lot of coded language that can convey implicit biases. But it seems impossible to not discuss and evaluate candidates based on personality. I mean, if the decision was based solely on qualifications, we’d just hire based on their portfolio and the actual interviews would not be necessary, right? Both the Zoom interviews and campus visits are incredibly informative in terms of a candidate’s capabilities (they do research talks, teaching demos, in addition to interviews). I think it’s unreasonable to not be able to mention that a person was really enthusiastic, energetic, invested or whatever descriptor. I mean, being a professor involves being able to connect with students, convey information accurately, and work alongside collaborators and colleagues, all of which would get conveyed through behavioral and/or personality traits. I plan to request a department meeting to discuss specifically what people mean by “personality” and what should (or should not) be discussed when evaluating candidates. There’s a part of me that thinks it’s unreasonable to avoid discussing “personality” of candidates, especially as relevant to the job, but am open to the possibility that I’m wrong or missing something. Do you have any thoughts about how to disentangle these issues or discussion points I can make during a department discussion? Connect those descriptors to the work itself so that you’re demonstrating relevance. So it’s not “she was really charming” — it’s “she had a warm and energetic presentation style that kept the audience engaged with the material.” And it’s not “he seemed kind of boring” — it’s “during his presentation, he read off his slides and didn’t engage with the audience and my sense was people were tuning out.” So it’s not about who they are; it’s about drawing connections to their actual work. Related: how do I ask references about a candidate’s personality? 4. How much can I share with a new job about my horrible old job? I am a former federal employee (I had the flexibility to be able to choose to leave rather than be fired) who will be starting at an analogous state agency this month. [Insert huge sigh of relief for landing a job in my always competitive field in this job market.] My new position will interface with my former federal agency. The federal workplace has been notoriously difficult this past year. However, there are some specific circumstances that led to my choosing to leave the position that a year ago was my dream job. In addition to the general instability caused by full-time return to office, “5 things” emails, threats of reductions in force, firings, repeated rounds of resignations, and partner employees losing funding and being laid off (things most people are aware of), my last months of federal employment were particularly awful. I had a member of my immediate team die by suicide. This would have been traumatic enough, but it was exacerbated by state-level leadership’s decisions prior to their death and my being assigned their duties on top of my own with minimal support. I cried at my desk every day after until I was able to leave. A year ago, I was on a team of ten experienced federal servants; only three are still federal employees. This has caused a lot of trauma and turmoil in my private and work life. For the past six months, I have been working outside of my field (and going to therapy), which has given me some time and space to heal. I am unsure how much background to share when starting my new position. The general nods to how bad things are on the federal side don’t really capture the depth of what I’ve experienced. I will be moving forward with any interactions with federal partners with particular care knowing all of this context. Any advice on how/when/if to share my personal experiences with my new team would be greatly appreciated. I wouldn’t get into it in any level of detail until you know them better and they know you better. Rightly or wrongly, when someone new starts complaining about their old job right off the bat — even when those complaints are warranted and they’re 100% in the right — it can come off strangely and make people think you lack discretion (at best) or will be difficult to work with (at worst). The current situation with federal jobs is a little different because everyone knows what’s been going on there, but I’d still err on the side of discretion about the details. Once you know people better and have established yourself as someone competent with good judgment, you can start to share some of the specifics. 5. How do I refer one former employee but not the other? I managed a tight-knit team at my old company and, like a lot of people in my field, the whole team got laid off last year. We’ve all kept in touch and so I know that one of them, Alex, is still looking for work. We’re about to have a job available at Alex’s level, but I wouldn’t recommend them. They were lacking some basic skills and despite coaching, if the company lasted longer, they might have been on a PIP. But another one of my reports, Jen, is someone I’d love to work with again and this role would be a step up. I’d be happy to refer her, but she might ask if I’ve referred Alex since she also knows his situation. It feels inappropriate to tell her his skills aren’t up to snuff for the role. (I also know he’d be offended if she got a new job working with me and he wasn’t even approached, but that’s a different matter of talking to him when it comes up.) Is there a way to refer her in without lying or violating his privacy? If she asks if you’ve referred Alex, you can say, “I don’t think he’s as well-matched as you are with what they’re looking for, but I’m keeping an eye out for anything I do think he could be good for.” The post our employee misses too much work, boss is different in person, and more appeared first on Ask a Manager. View the full article

-

Coca-Cola scraps Costa Coffee sale after bids fall short

Coke had been seeking about £2bn after paying £3.9bn for UK coffee chain in 2018View the full article

-

Crispin Odey to make hedge fund dormant

Odey Asset Management plans to ‘cease trading activities’ follows founder’s fall from grace over sexual misconduct claimsView the full article

-

The Maga war on European democracy

America’s national security strategy projects internal fears abroadView the full article

-

‘Welcome to hell’: Venezuela’s most notorious torture chamber

Families call for release of political prisoners at the brutal El Helicoide jailView the full article

-

How Iran switched off the internet — and Iranians fought back

Tehran went from ‘halal internet’ to near-total blackout but activists have smuggled in Starlink devices to get information outView the full article

-

Inside the US justice department’s probe of Jay Powell

Investigation into Federal Reserve chair’s testimony raises questions around the independence of the country’s judicial armView the full article