Everything posted by ResidentialBusiness

-

How To Get A Job In Digital Marketing In 2025

Facing challenges in your job search? Explore strategies to help you secure a digital marketing job despite tough times. The post How To Get A Job In Digital Marketing In 2025 appeared first on Search Engine Journal. View the full article

-

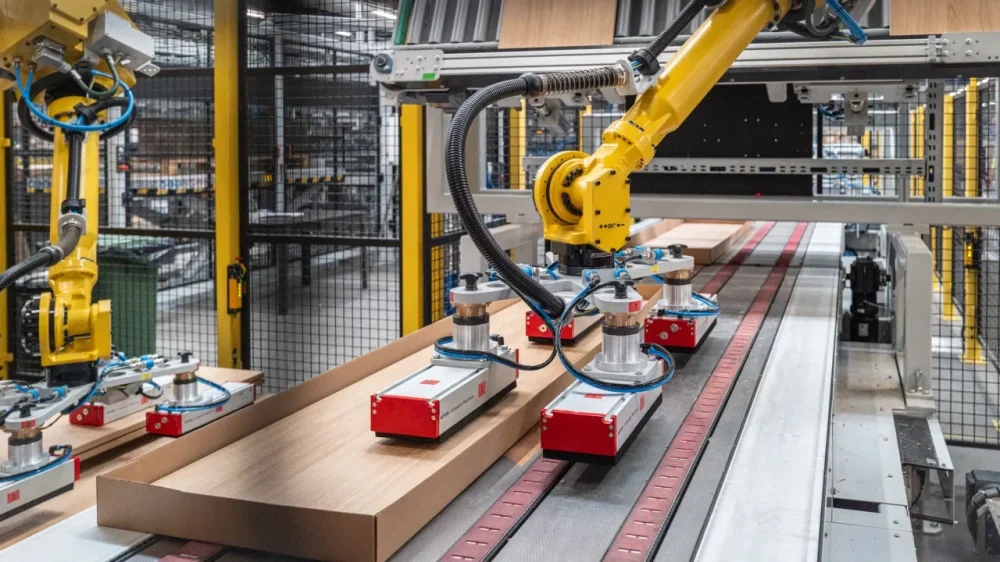

How Ikea turned flat-pack furniture into a business worth billions

It doesn’t take long for Christer Collin and Ola Wihlborg to assemble the newest credenza from Ikea. Collin is a 42-year veteran of the company, specializing in product development. Wihlborg is one of the company’s most senior designers, having created dozens of pieces of furniture sold by the retailer since 2004. The two Swedes are lifting parts and turning hex wrenches in a second-floor conference room in Trnava, Slovakia, just outside the capital, Bratislava. This is where Inter Ikea Group (one of two Ikea parent companies) operates one of its more than 30 furniture and furnishings factories through its subsidiary, Ikea Industry, and where a sizable number of the retailer’s most commonly purchased items materialize. The credenza is one of Wihlborg’s own creations, and it has just come off the line of the sprawling factory downstairs. As he works, he’s barely consulting the detailed paper assembly manual familiar to anyone who’s put together a piece of Ikea furniture. “I can do it without, but it’s always nice to see the instructions,” Wihlborg says between sips of coffee, a model of Scandinavian cool in a black baseball cap and T-shirt. He has the design of the piece deeply ingrained in his brain after a three-year development process that’s brought it from concept to commercialization. Collin is an Ikea supply innovator whose job is to streamline how the company designs its furniture for customer assembly, and he’s visited dozens of Ikea factories and suppliers throughout his career. He can build with surgical precision. And because of the unique way Ikea has come to be such a dominant and global-scale furniture retailer, Wihlborg and Collin also know pretty much exactly how this credenza has been produced, down to the milling of the rails for its sliding doors and the location of the dowels that hold its sides in place. To a degree, most of Ikea’s 899 million annual customers probably don’t appreciate how the making of a piece of furniture like this credenza is a finely calibrated dance involving design, manufacturing, packaging, and assembly, with each element influencing the others in equal measure. Ikea’s designers must know how to make a piece of furniture, but also how it will be produced en masse, how it will end up on a shipping pallet, and how an untrained consumer can put it together without ripping their hair out. This interrelated process is the Ikea way, dating back to its world-changing leap into the self-assembled furniture business in 1952, and foundational to its global success. At the end of its 2024 fiscal year, Ikea parent company Ingka Group reported annual retail sales of 39.5 billion euro, or roughly $44.8 billion. Its share of the $940 billion global home furnishings market is a remarkable 5.7%. More than 727 million people visited its stores in 2024. It used about 473 million cubic feet of wood for its products, a figure that’s often compared to about 1% of the wood consumed around the world per year. As a company, it is an undeniable global force. It’s also been uncommonly influential in the business world. Though it did not invent flat-pack furniture, also known as knockdown furniture, it has so thoroughly saturated the market that all its biggest competitors, from Wayfair to Walmart, must do the same. Flat-pack furniture represents an $18 billion global market, a market many analysts expect to grow more than 50% over the next decade. Wihlborg and Collin have Ikea’s design-manufacturing-packaging-assembly calculus hardwired into their brains. Within 24 minutes of opening the credenza’s two boxes, they have the piece fully built. And though Wihlborg has run this design through his mind countless times over roughly three years of development—with concepts, prototypes, factory adjustments, revisions, and tiny tweaks—he had to come to this Slovakian factory to unbox and build the final product. “It’s actually my first time,” Wihlborg says, smiling. Inside Ikea’s factoryEverywhere you look across the cavernous floor of Ikea Industry’s Trnava factory there is particleboard, often standing several feet high, and in hundreds and hundreds of stacks. Piled on racks that traverse the factory’s football-field-length halls on a network of rolling steel conveyors, these precisely processed cuts of particleboard come in a variety of densities and more than 20 different base dimensions. They get worked by hand, machine, and, increasingly, robot, to transform into the building blocks of some of Ikea’s best-selling shelves, tables, and chairs. Through a nearly scientific process, they’ve been refined to the size and form that simultaneously fit the intentions of the design concept, the capacities of the factory’s equipment, and the confines of a cardboard box a typical consumer can lift into the back of a car. The Trnava factory is one of Ikea’s flat-pack furniture powerhouses, running around the clock with 500 workers, three eight-hour shifts, and an active floor covering more than half a million square feet—twice the size of a typical Ikea store. It pumps out about 25,000 pieces of furniture every week. Its warehouses are stacked with assembly-ready boxes filled with Billy bookcases, Tonstad storage cabinets, and Hemnes bed frames. Since October, the Trnava factory has also been producing about a dozen of the furniture pieces that make up Stockholm 2025, Ikea’s newest line of high-end furnishings, including Wihlborg’s credenza, which retails for $400. Its path through the factory—from raw particleboards to milled and veneered pieces to flat-packed final product—is a case study in the ways design, production, and packaging cross-pollinate to create the Ikea products that end up in homes all over the world. It’s a process that starts with one of those stacks of particleboard. Workers in rubber gloves move wide rectangular boards onto a work surface, where one lays down a line of glue and the other mallets a strip of solid oak into a narrow slit. This piece will be the base of the credenza, and the length of solid wood will soon be sawed and milled with tiny channels for the credenza’s sliding doors—a higher-quality detail than the tacked-on plastic or aluminum rails that might be used in lower-cost products. The credenza’s baseboard then heads off to another station, where a worker spends a full shift guiding close to 800 baseboards through a sanding machine that makes the glued oak piece exactly flush with the rest of the board. At the same time, a massive saw machine cuts down large sheets of particleboard to component size, before being automatically sorted and grouped for further processing. The sideboards, the interior shelves, the bottom supports, and the top all get cut and stacked and moved down the line. Pneumatic machines with grids of suction cups lift individual boards onto conveyor belts where they’re sprayed with glue, topped with wood veneer, and pushed into the hiss of a heated pressure machine. After seven seconds, they come out the other end with an aesthetically pleasing hardwood look, despite their cheaper and lighter particleboard innards. After edge shaving in one machine, another machine hot glues a strip of veneer around their perimeters, covering any hint of the base material inside. These processes are being done in rapid, automated succession via complicated machines that are bigger than some people’s apartments. The Trnava factory has been chosen to produce this specific product because it has the capability of pulling off the higher-end details. This path through the factory line is one Ikea designers often follow from the earliest stages of their design development. They’ll tour Ikea-owned factories like this or the roughly 800 independent suppliers that produce the furniture, dishware, picture frames, and toilet cleaners that are sold in Ikea’s 481 stores in 63 global markets. What a given factory can make often helps shape a product’s design, and the design can push the factory to adopt new technologies and production methods. A long shelf in the new Stockholm collection, also designed by Wihlborg, used a minimalist framing system that required extra strength in the fittings connecting the horizontal shelves to the uprights. Through a series of consultations, prototypes, and samples sent back and forth from Trnava to Ikea’s headquarters in Älmhult, Sweden, the design and factory teams landed on a unique, diagonally milled solution. “We very much appreciate these challenges,” says Marek Kováčik, site manager at the Trnava factory. “We never say no.” The flat-pack formula“It’s not only the product that has to be beautiful. The production has to be beautiful,” says Johan Ejdemo. As Ikea’s global head of design since 2022, he’s acutely concerned with the look, quality, and sales of the 1,500 to 2,000 new products that make their way into Ikea stores every year. As a trained cabinetmaker who’s spent years inside a carpentry shop, he’s also attuned to the realities of actually producing those products, and the compromises that sometimes have to be struck between design intention and material reality. “There needs to be this rhythm. It’s almost like a dance. It has a certain tempo. It has a certain flow,” he says. That dance is sometimes led more by a product’s design, at other times by the factory’s table saw tolerances, and at other times by the economics of cramming a coffee table’s parts into one box instead of two. Always, since the earliest days of Ikea as a furniture retailer, the end cost to consumers is the ultimate guide. “First of all, we have the mission that we need to be smart with resources because we need to keep costs down. Because keeping costs down will enable a lower price, and the lower price will make more people able to afford it,” Ejdemo says. “It’s taking top-shelf things and moving them down a few steps so they’re easier to reach.” This approach to what Ikea calls “democratic design” has been baked into the company’s DNA since it evolved from a provincial mail-order catalog in the 1940s to a home furnishings retailer by the mid-1950s. Its unique perspective on design, production, and packaging is all connected by the fundamental philosophy of self-assembly that has turned Ikea into a global behemoth. Company lore has it that the light-bulb moment came around 1952 when Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad and early Ikea employee Gillis Lundgren were wrapping up a photo shoot for a new Ikea catalog and they needed to move a bulky table. Lundgren noted how much simpler it would be to store the table if the legs could just come off. Kamprad realized that furniture would be so much easier (and cheaper) to sell through his mail-order business if it left the factory disassembled and as flat as possible. In Leading by Design: The Ikea Story, a 1998 book coauthored by Swedish journalist Bertil Torekull, Kamprad writes that this became the basis for how the company approached all its products. Kamprad, who died at age 91 as a self-celebrated penny-pincher, summarized the Ikea way as “a design that was not just good, but also from the start adapted to machine production and thus cheap to produce. With a design of that kind, and the innovation of self-assembly, we could save a great deal of money in the factories and on transport, as well as keep down the price to the customer.” Over the decades, this thinking has become inextricably connected to every stage of Ikea’s product development, which Ejdemo says has been helped along by better design tools, new factory technology, and innovative fittings to improve self assembly. Particleboard can be engineered to have higher density in the places where screws will make connections and lower densities elsewhere to bring down the total weight. An internally developed “wedge dowel” allows some parts to be snapped together without any screws. The company has even adopted a technique from orthopedic medicine in which snap-together elements are ultrasonically welded into wooden pieces, forming a tight connection that allows parts to be assembled and disassembled repeatedly. Collin, who helped integrate this solution, says the company had been looking at ultrasonic welding for other purposes, but it ended up being a perfect way to integrate the hardware of a furniture piece. “The inside of a bone is quite similar to particleboard,” he says. Operating at such a large scale in markets all over the world, Ikea’s product developers learn to internalize the interconnected nature of designing for the factory, the box, and the end user. Ejdemo, who started at Ikea in 1999 as a product engineer, says designers come to have three numbers in their minds at all times: the 80-centimeter width and 120-centimeter length of the shipping pallets that carry boxed products from factory to store, and the 25-kilogram weight limit (about 55 pounds) the company has for those boxes. Some might call this a curb on creativity, but Ejdemo sees it pragmatically. “I need to consider this because it will be considered anyway at some point,” he says. “If you’re not on top of it as a designer you might see things happening that you wouldn’t want to happen from a design perspective.” Achieving massive scaleWalking through the Trnava factory’s vast halls, production manager Michal Puškel bends down periodically to pick up a stray piece of packing tape or paper from the floor. The factory is impeccably clean, despite stacks of particleboard snailing their way across acres’ worth of conveyors, and high-speed saws, mills, and drills cutting through boards by the thousands. The factory has been operating here since 1990, back when this was still Czechoslovakia and Ikea was making inroads into formerly communist countries. Over the years, the Trnava factory has been thoroughly modernized, with long chains of automated machines and a growing number of robotic arms deployed throughout. Puškel seems to know each machine just as well as the many workers he stops to chat with on his way down the production line, highlighting their unique capabilities and stepping over components to point out the best view. At the end of one machine’s conveyor, he leans over a rail and pulls off a processed board, one of the bigger parts of the credenza the factory is currently producing by the hundreds per day. With his finger he touches the places where, within seconds, the machine has milled small notches where other pieces will soon be attached, and it’s also drilled the precise holes that customers will use to complete the final assembly—the sweat equity that keeps Ikea prices low. The Trnava factory specializes in this type of particleboard and veneer manufacturing, known as flat-line production, where each piece moves down the line and slowly gets turned into a more refined part of a piece of flat-pack furniture. But some items require more attention to detail, including several of the pieces the factory is making for the new Stockholm line. One is the long shelving unit Wihlborg designed after a lengthy back-and-forth with the factory over how to connect its shelves to its upright supports. The solution they came up with—a somewhat complex hole milled at a 45-degree angle into the upright supports in order to conceal the hardware in the finished piece and maintain strength—requires each shelf and upright to get processed by a massive computer numerical control (CNC) milling machine. Crossing the factory to a bright and noisy corner, Puškel shows off a cluster of CNC machines that can take each of those shelving unit’s pieces and mill the angled hole, perform multiple cuts using a menacing multiblade saw arm, and smooth out the radii to ensure the pieces come together snugly. Nearby, a worker has a recently milled board up on a table with a measuring tape, and he’s consulting a diagram as he checks the size of each hole and groove. “We inspect every hour,” Puškel says, with his own eye on the inspector. Other parts of the factory have a visual system to check for less-intricate mistakes, like chipped corners or misaligned veneers; if it sees a problem five times in a row, it automatically shuts down the line. Mistakes happen, and Puškel says it’s critical to keep a close watch on the line any time it starts up on a new batch of one of the hundreds of furniture types the factory produces. But it doesn’t take long for the factory to find its groove. “After a half hour, everything will be stable,” Puškel says. Then it will be ready to keep pace with Ikea’s massive globe-spanning scale. The big business of logistics Ikea has a business imperative to pay so much attention to the intricacies of how every piece of furniture is designed, made, and packaged. Craig Martin, a professor of design at the University of Edinburgh, has written extensively about mobility and design, from shipping containers to the cardboard blocks used to fill empty space in Ikea furniture boxes. He says Ikea is uniquely concerned with these mundane details. “In the traditional design process, packaging is a bit of an afterthought. With Ikea, packaging design and logistics were very much part of that same developmental process. I think that’s one of the most interesting things about Ikea,” Martin says. “I’m not aware of many other manufacturers or companies who are so invested in logistics the way Ikea is.” The reasoning behind it is cost, Martin says, which has been key to Ikea’s ability to gain such a large share of the furniture market. “It’s about the economics of it. If you can save money by building logistics and packaging design into the design process, then that’s the crux,” he says. As a company with tens of thousands of employees worldwide, Ikea has plenty of specialists who make sure packaging is optimized and logistics are efficient. But these concerns have also trickled down throughout the design and product development pipeline, and designers like Wihlborg can conceptualize their design as both a built and a flat-packed product. “During the process, of course we think about how to knock down the product and pack it in a flat pack, so we don’t go into something that is impossible,” Wihlborg says. “We always have it in mind.” Flat-packing concerns shape decisions far beyond the look or size of individual items. Karin Gustavsson, creative leader for the Stockholm 2025 collection, says the close collaboration between designers and factories helps ensure these efficiencies are identified as early as possible. “If you see that it helps to make the table 10 centimeters smaller in length, then we need to start over to do new samples and try it and ask is it okay to just shrink it in length or should we change anything else,” she says. “All this is in the design process.” These considerations end up playing a surprisingly large role in determining the design of Ikea’s products. For example, the dining table Wihlborg designed for the Stockholm 2025 collection used one density of wood where its legs attach, a lower-density around the perimeter, and a nearly hollow but structurally sound honeycomb-shaped cardboard filler for the center—an approach that reduced its overall weight while reducing its risk of bending. It also meant the tabletop wouldn’t need a supporting frame underneath, cutting material use, the total number of boxes the product fits in, the overall cost to customers, and the carbon emissions required to ship it. “Those things we can simulate very easily with computerized design,” Gustavsson says. Some have criticized Ikea for optimizing its design for cost, arguing it creates a kind of disposable furniture that sacrifices durability for rock-bottom prices. The Lack side table, now retailing for $12.99, is one common scapegoat. It is also a perennial bestseller. With thousands of products on offer, Ikea’s range of quality is inevitably going to be wide, but Gustavsson says the company is trying to prove that it can hit new heights in quality without getting too far out of the common person’s price range. “We don’t believe in fast fashion always. We’ve tried to make Stockholm very high quality and long lasting. It has been the mantra for us to show that Ikea could really be this high-end furniture,” Gustavsson says. “We’ll also attract a new customer, we believe.” The company is also trying to counter the disposable-furniture criticism by prioritizing design for both assembly and disassembly, allowing customers to more easily pack up a piece of Ikea furniture and move it to a new place instead of leaving it on the curb. Collin, who was part of the team that developed the snap-in-place wedge dowel, says the move is toward “enjoyable assembly,” and new fittings and assembly techniques are part of making that possible. He points to studies the company does of people’s expectations of how long it will take them to build a given item. “With the old fittings”—think screws and hex wrenches—“it always took double what they expected,” Collin says. Now, with pieces that snap boards together instead of chip-prone nailings or patience-draining hex screws, more and more products have milled wedge dowels that snap and lock into place and easily placed plastic fittings that hold a bookcase backing tight without a single nail. “We always try to be better and better on assemblies. You should feel like you made it in the time you expected,” Collin says. If a product is easier to build, he says, it should be easier to take apart as well. This thinking is making its way across Ikea’s design portfolio, according to Ejdemo. “The whole system change toward circularity will demand a lot of us. How will things be packed and distributed and how will you be able to resell, repair, give a second life, upgrade, update,” he says. “There’s more involved in this than the products, but it will require shifts and new thinking into the products to enable that to happen.” Near the end of the production line inside the Trnava factory, the 16 individual wooden pieces of the credenza are all processed and finished, with their uniform oak veneers and precisely aligned dowel and screw holes. They’ve been wheeled or forklifted over from various parts of the factory to the flat-packing area, which has become one of the busiest and most dynamic parts of the facility. Here Kováčik, the site manager, points out the facility’s newest pieces of equipment: a set of five-axis robotic arms that are currently being programmed to perform the Tetris-like job of fitting every part of an Ikea product into a tightly packed box—and in the right order. “It’s done in consecutive steps, according to the assembly instructions,” Kováčik says. The new robots are doing the heavy lifting, grabbing the largest pieces of the credenza and laying them inside the bottom of a box another machine has just finished folding and gluing. Down the line, two human workers neatly place a few of the smaller wooden pieces in the box before it moves on to another group of workers who lay down other parts of the credenza. Each one goes in a specific place, with the narrow gaps of negative space filled in with strips of thick cardboard, placed down by hand. By the time each worker has laid their pieces in the box, another is coming toward them on the conveyor belt. Puškel, the production manager, says the robots will eventually be able to plop in even the smaller parts of a furniture item, reducing the need for workers to stand by and place parts in boxes over and over again. He lists out the downsides of such rote human labor: ergonomic risks that can hurt workers, worker sick days that can hurt productivity, and human salaries that hurt the bottom line. Kováčik assures that any work a robot takes over simply creates opportunity for human workers to do something more worthwhile. One job no robot will soon take over is the designated assembly inspector, who spends their shift picking out 10 to 12 finished furniture pieces from the assembly line, opening their boxes, and putting them together, like an Ikea customer outfitting a new apartment. On this day, the inspector on duty takes a little more than 10 minutes to mostly build the credenza, looking for the main issues of chipped corners and mismatched veneer colors. Once it’s passed, the inspector takes the pieces apart and places them neatly back in their boxes to join the rest of the day’s output. Stacks of these boxes make their way to another set of robots that carefully arrange them on pallets that will be shipped around the world and placed in the warehouse-like “self-serve” sections of Ikea stores. One last refrigerator-size machine reaches out a robot arm and slaps the palletized boxes with identifying labels. “Now,” Puškel says, with a nod, “it’s finished.” A long-term relationshipBack in the factory’s second-floor conference room, Collin is sitting on the credenza he and Wihlborg have just assembled. “I’m not the heaviest TV,” he says. His point is that this is a piece of furniture that’s meant to perform, withstanding all the reasonable and sometimes unreasonable conditions it will be thrust into when it ends up in a living room in Tulsa, Oklahoma, or Guangzhou, China. For all the ways Ikea furniture is designed for the back end—for the company’s design intentions, for the supply chain and production process, for the complex logistics of global domination—it is, ultimately, something that will live in people’s houses for years or decades. The way the furniture is designed, produced, and shipped is interconnected in an increasingly complex way. But the goal remains quite simple: to create furniture that people will use. View the full article

-

What is a ‘pink tariff’? A gender tax exists in global trade, too

Since President Donald The President unleashed an onslaught of import taxes on countries around the world, the word tariff has entered the collective vocabulary, and with it reciprocal tariffs, retaliatory tariffs, compound tariffs, and most-favored nation tariffs. But here’s one you may not have heard before, even though it’s been around for decades: the pink tariff. Pink tariffs add a roughly 3% U.S. tax onto the price of women’s clothing compared to the same products made for men, according to CNN. How do pink tariffs work? Research shows that tariffs don’t affect everyone equally. In 2018, a U.S. International Trade Commission study found that women pay more than men for gendered product categories like clothing and shoes, as reported by Politico. That’s because the Harmonized Tariff Schedule, which creates U.S. tariff rates on U.S. imports, classifies footwear and apparel by gender, per CNN. “It is very strange and hugely inappropriate that the U.S. government should be having differential tax rates that attack women more than men for essentially the same things,” Ed Gresser, vice president and director for trade and global markets at the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI), told Politico. For example, Gresser looked at tariff rates for women’s clothing in 2022 and found they were 16.7% higher than men’s, at 13.6%. How will The President’s trade war affect pink tariffs? Notably, The President’s disruption of tariff policy does not extend to pink tariffs, which are being left in place. As women’s clothing will continue to be taxed at a higher rate than men’s, the tariffs The President is placing on China and potentially other countries could hit female consumers in the U.S. harder than their male counterparts. Women in the U.S. were already paying “a kind of gender surcharge of at least $2 billion a year,” according to the PPI. Add on The President’s tariffs, and that number will likely go up. For now, women will need to wait and see by how much. Although The President has currently paused tariffs on all countries for 90 days—except China, which now faces a whopping 145% tax on imports to the U.S.—many companies aren’t waiting to see the effects; they’re increasing their prices and passing those costs on to consumers. It’s now common to see “tariff surcharges” on company invoices and websites. View the full article

-

He built an AI app to beat coding interviews. Then Columbia suspended him

A software application called Interview Coder promises to help software developers succeed at technical job interviews—by surreptitiously feeding them answers to programming questions via AI. Interview Coder’s 21-year-old cofounder and CEO Roy Lee says he and Neel Shanmugam, the company’s cofounder and COO, created the tool partly as a protest against longstanding industry practices that require job candidates to solve programming puzzles during interviews. Lee, who until recently was a sophomore at Columbia University, says he spent hundreds of hours practicing such problems—time that could have been spent on actual coding projects. “This kind of killed a lot of my love for programming, just because I was forced to write code that just wasn’t fun,” he says. “I was forced to solve riddles instead of actually working on building real world projects, and I just grew to really dislike the system.” But protest or not, Lee says the project has proven lucrative, recently surpassing $3 million in annual recurring subscription revenue—presumably from customers more interested in cheating their way into a job than making a statement. The program, available for Windows and Mac, allows users to secretly take screenshots of programming puzzles presented during interviews, feeding the questions to AI for analysis and coded solutions. The software is designed to evade detection by anti-cheating measures in interview platforms. Controlled by keyboard shortcuts, it avoids the giveaway of mouse movements. Interview Coder can even be placed transparently atop the interview window, so users don’t appear to shift their gaze while consulting AI-generated solutions and talking points. Lee recommends that users practice with the tool before deploying it in a real interview. Lee says he personally tested the software in real internship interviews and has posted videos online that appear to show him using Interview Coder during a challenge for Amazon. “We posted videos of me using it on Amazon, primarily, which is like the big boss interview that we took down,” he says. According to Lee, that led to takedown attempts by Amazon and disciplinary action from Columbia. He says the university initially placed him on probation over concerns that the tool could be used to cheat on class exams, then suspended him for a year for recording a disciplinary hearing and sharing related documents without permission. Lee says he’s unsure if he’ll return to school. He has published marked-up versions of Columbia documents related to the matter. The university declined to comment, citing federal privacy law, and Fast Company was unable to independently verify the authenticity of the documents. Amazon also declined to comment on Lee or his application but said, through spokesperson Margaret Callahan, that candidates are generally asked to acknowledge they won’t use unauthorized aids like generative AI during interviews and assessments. For his part, Lee believes big tech interview processes should better reflect actual working conditions. “It doesn’t make sense to test someone on riddles and essentially give them an IQ test when they’re not going to be doing that at all,” he says. In his view, job candidates should be allowed to use any tools they’d have access to on the job—including AI—during interviews. Having an AI copilot during an interview isn’t a completely far-fetched concept. Some technical interview platforms, like CoderPad and CodeSignal, already allow clients to enable AI assistants for candidates. But, says CodeSignal CEO Tigran Sloyan, that typically involves redesigning interview questions to suit AI usage and even revising job descriptions to reflect that AI proficiency is part of the job. He likens the transition to the introduction of digital calculators in schools, which eventually led to rethinking how math was taught and tested. It’s also critical, Sloyan adds, that companies provide the AI tools themselves rather than letting candidates bring their own. “Right now there is a gigantic menu of all sorts of different AI tools, some of which are very expensive to use, and there is a significant difference in what they can and cannot do,” he says. “So especially in the hiring process, when you want to give everybody a consistent and fair shot, the AI has to be embedded in the interview and assessment platform itself.” Sloyan also suggests Interview Coder may not be as stealthy as its creators claim. Beyond the technical countermeasures platforms like CodeSignal use to detect cheating, candidates might also give themselves away by awkwardly reading answers from a hidden window—behavior that differs from natural brainstorming. “I would highly encourage candidates who are going through an assessment process with CodeSignal to think twice before using something like Interview Coder, because we flag it countless times, and the claim that it’s completely undetectable is not true,” he says. Lee acknowledges that, at least for now, his software might help people cheat into jobs they wouldn’t otherwise land—or get caught trying. “Sure, there will be some bad eggs that get caught or that just slip in,” he says. But Lee—who’s exploring other applications for screen-aware AI assistance—argues that Interview Coder is ultimately meant to make itself obsolete by pushing companies to modernize how they evaluate candidates. “The product is meant to kill itself,” he says. “And the day it kills itself is the day that every single company will hire significantly better engineers, and every engineer will be better because they’ll spend more time engineering instead of [solving programming puzzles.] It’ll just be a huge net positive for the developer community.” View the full article

-

House Republicans want to gut Medicaid. In California, that could cost them their seats

House Republicans passed a budget plan last week that could slash up to $880 billion over 10 years from Medicaid, a program that provides health insurance to 83 million low-income Americans. For the past several months, healthcare advocates have been ramping up pressure on three vulnerable California Republicans in Congress—Representatives Ken Calvert, Young Kim, and David Valadao—urging them to break ranks and reject those cuts when the final budget comes up for a vote in the coming months. All nine of California’s Republican representatives voted in February to advance the GOP’s budget blueprint, which calls for massive cuts to Medicaid. But of the nine, Calvert, Kim, and Valadao won their seats in 2024 by the narrowest margins—3, 11, and 7 percentage points, respectively. Healthcare advocacy groups and unions that represent healthcare workers are hoping to take advantage of their vulnerability by energizing voters in their districts to demand they vote against Medicaid cuts or else face massive backlash when up for reelection in 2026. The campaign is being spearheaded by advocacy groups Health Access California and Protect Our Care, as well as We Are California, a coalition of state and local community organizations. United Domestic Workers, which represents more than 170,000 home care and childcare providers in California, and the Service Employees International Union, which represents more than 2 million service workers across the country, are also playing a leading role in the campaign. (Disclosure: The SEIU and United Domestic Workers are both financial supporters of Capital & Main.) Capital & Main Those groups have organized protests in front of the district offices of Calvert, Kim, and Valadao; coordinated letter-writing campaigns; aired digital and TV ads; and hosted town halls at which constituents speak about the importance of Medicaid, which is known as Medi-Cal in California. Though the representatives have been invited to attend those town halls, none have. The campaign aims to mobilize voters like Cynthia Williams, who attended a March protest outside Kim’s Anaheim office. She told the hundreds in attendance that she felt betrayed by the congresswoman she had supported. “It was like a slap in the face,” Williams said. “It was like somebody saying, ‘You don’t matter. Your family doesn’t matter.’ We helped vote to get this lady in there and this is what we get? It’s wrong. It’s totally wrong.” Cynthia WilliamsCapital & Main Williams voted for Kim in 2024, believing that the Republican congresswoman was “on the same page with us as far as Medicaid.” But after the congresswoman voted in February to advance a budget blueprint that would slash the program, Williams became an outspoken critic of Kim. Williams’s full-time job is taking care of her adult daughter Kailee, who is blind and has an intellectual disability and cerebral palsy, and her sister Shanta, who is a veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder and other severe mental disabilities. Both Kailee and Shanta receive funding from In-Home Supportive Services, a public program in California that provides support to more than 700,000 low-income Californians with disabilities or who are 65 and older by funding caregivers like Williams. Because In-Home Supportive Services receives most of its funding from Medicaid, many fear cuts would reduce or even eliminate programs that support people with disabilities. Capital & Main That’s why United Domestic Workers, of which Williams is a member, has joined in the efforts to pressure vulnerable Republican representatives against voting to cut critical healthcare funding. And according to Doug Moore, UDW’s executive director, the pressure campaign is only getting started. “We have just begun to apply the pressure. We have not turned it up yet. We’re on simmer as far as I’m concerned,” Moore said in March. “We are going to be relentless with pressure on them . . . and we will continue to target them until 2026 and beyond.” If Moore and other advocates are able to exact a political price from vulnerable Republicans who vote to cut Medicaid, it wouldn’t be the first time a California swing-district GOP representative lost an election because of healthcare policy decisions. In 2018, Valadao lost his seat shortly after voting to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which significantly expanded Medicaid. The congressman later regained his seat in 2020. This time around, Valadao signed onto a letter urging Republican House leadership not to cut Medicaid, a move that political strategist Steven Barkan views as a sign that some GOP lawmakers understand that cuts to healthcare funding are politically toxic. “It is very dangerous for Republicans, especially those in swing districts,” said Barkan, whose political consulting firm, Barkan Strategies, works with Democrats. “If they don’t stand up to the cuts, then they are vulnerable. They could conceivably lose the House majority over Medicaid.” In a January poll conducted by YouGov, only 17% of Americans supported cutting Medicaid funding. Healthcare advocacy groups have emphasized that figure in pressure campaigns targeted at Republican lawmakers across the country. The strategy of focusing on Republicans’ support for Medicaid cuts may be working. Democratic candidates have significantly overperformed in special elections held since November’s general election. Barkan said fears regarding Medicaid could be contributing to Republicans’ recent lackluster showings, although he added that it’s too early to be certain. Calvert, Kim, and Valadao have all expressed concern about the effects of cutting Medicaid, even after voting in February to advance the GOP’s budget blueprint demanding just that. On Thursday, Kim and Calvert both voted to approve a revised congressional budget blueprint that maintained sweeping cuts to Medicaid. Valadao did not vote on the bill. In February, Valadao said he would not support a final reconciliation bill that would risk leaving behind people who depend on Medicaid. On February 26, Kim posted a statement to her website saying she would not vote for “a budget that does not protect vital Medicaid services for the most vulnerable.” In a March 19 Instagram post, Calvert wrote that he was “committed to protecting Medicaid benefits for Americans who rely on the program.” Barkan said that the fact that Calvert, Kim, and Valadao are “talk[ing] out of both sides of their mouths” is a sign that they are feeling the heat. The pressure campaign is putting the congresspeople in the increasingly difficult position of choosing between what their constituents want and what their party leadership wants, he added. “The more they see their own base reacting, the more danger they will see,” Barkan said. “They have to figure out which is more harmful to them: standing up to The President or screwing over their constituents.” Calvert, Kim, and Valadao did not respond to requests for comment. The protests aimed at applying that pressure have been attended by people from across the political spectrum, according to Jonathan Paik, executive director of OC Action, a progressive advocacy group and partner organization of We Are California. Paik attributed the broad turnout to the bipartisan consequences of proposed Medicaid cuts. He added that the shared frustration among Democrats and Republicans provided a powerful organizing opportunity. “The sheer scale and visibility is going to be materially felt all across Orange County,” Paik said. “This has been a moment for us to be able to help folks understand who would unilaterally benefit from these cuts: the billionaires.” The GOP budget calls for Medicaid cuts to offset tax cuts that would disproportionately benefit the wealthy. Gerald Kominski, senior fellow at UCLA’s Center for Health Policy Research, said voters will likely see that tradeoff as “blatant robbing from the poor to support the rich.” —By Jeremy Lindenfeld, Capital & Main This piece was originally published by Capital & Main, which reports from California on economic, political, and social issues. View the full article

-

The 2026 Winter Olympic torches let the flame steal the show

The torches designed for Milano Cortina 2026, next year’s Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games in Italy, were made in service of the flame. Named Essential, the reusable, ultra-minimalist torch has a flared, open-top design meant to show viewers how the flame is generated because “what’s important isn’t the torch, but the flame,” Italian architect and engineer Carlo Ratti tells Fast Company. The design is meant to showcase the flame in motion. “The open-top design is crucial to how the flame comes to life,” explains Ratti, who designed the torch with his eponymous firm, Studio Carlo Ratti Associati. The torches were developed by Eni and Versalis, both official supporters of the Games, and the Italian manufacturer Cavagna Group engineered their production. Each torch has an air intake near the upper cone that allows oxygen to mix with bio-gas, “generating a warmer, more natural yellow flame—one that aligns with the Olympic spirit far better than the cold, blue flame of many torches,” he says, adding that it was tested in wind tunnels and real-time trials. “When the torch is in motion, that same openness helps produce what we call the ‘flag flame,’ a dynamic, horizontal flame that trails behind the torchbearer while running,” Ratti says. Milano Cortina 2026 Olympics The 2026 Games bills itself as the most widespread ever, since it’s the first Olympic Winter Games to be named for two cities, Milan and Cortina, and will be held across multiple regions in northern Italy. That’s a geographically big Olympics, but the design of the Essential torches communicates an opposite message of minimalism, of doing more with less. The torches are lightweight, about 2 pounds each without their fuel canisters, which can be refilled and reused as many as 10 times. That reduces the overall number of torches that need to be produced for the 63-day Olympic Torch Relay, which begins this November 26, ahead of the Opening Ceremony on February 6, 2026. The torches’ burners run on fuel made from renewable materials like cooking oil, and they’re made with recycled aluminum and brass alloy coated with a reflective, iridescent finish in two hues—a turquoise blue for the Olympic Games and a lustrous bronze for the Paralympics. Milano Cortina 2026 Olympics The accoutrements of the modern Olympic Games give host cities the chance to show off their culture, industries, and style. That’s a unique opportunity to showcase a state’s heritage on a global stage, such as the Paris 2024 medals, which included pieces of the Eiffel Tower. But it also puts a magnifying glass on design mishaps—such as those same medals having to be replaced due to deterioration. For northern Italy, the Games are a chance to show off Milan’s status as a world leader in design. The torches were unveiled at both the Triennale di Milano, an art and design museum in Milan, and the Italian Pavilion in Expo 2025 Osaka in Japan. Raffaella Paniè, director of brand, identity, and the “Look of the Games” for Milano Cortina 2026, says the torches are named Essential because they make the most of the bare minimum, allowing the flame to steal the show. This same minimalist approach is setting the stage for the rest of the Games’s aesthetics. “If we consider Italian design, in line with our Italian spirit and wanting our brand to be vibrant, dynamic, and contemporary, we can expect future design elements, such as medals and the podium, to also reflect this aspect,” she says. View the full article

-

Inside the new tactile tech bringing basketball to blind and low-vision fans

Barclays Center in Brooklyn is abuzz as the Brooklyn Nets’s Jalen Wilson catches the ball, readies himself, and releases a contested three. The ball arcs high above the Knicks defender’s outstretched arms and swishes through the net. As the stadium erupts, Bryan Velazquez throws a fist in the air. Even though he is blind, he knows that his team just scored. He felt it on his fingertips. Velazquez, who works as an outreach coordinator at Omnium Circus, is using a new kind of haptic device that translates live game action into vibrations. Developed by Seattle-based startup OneCourt, the laptop-size device consists of a silicone relief map displaying a basketball court with the Brooklyn Nets logo at the center, and comes with hundreds of motors that vibrate to indicate the position of the ball on the court. People who are blind or low vision can lay their hands flat on the device and “feel” the ball move back and forth, while an earpiece provides live updates on the score and various play outcomes like “shot made,” “shot missed,” “out of bounds,” or “foul.” Every major sports league tracks the position of its players and the ball in real time using advanced optical and sensor-based systems like Hawk-Eye. OneCourt’s technology taps into that data over 5G and translates it into trackable vibrations that move across the surface of the device. These vibrations—think of as them as auditory pixels—vary based on the type of play unfolding on the court. When a player shoots, the corresponding location of the shot on the tablet vibrates more strongly. If the player scores, the motors underneath the hoop pulse vividly. If the player misses, the motors sigh one long, seemingly disappointed vibration. “I really hope a lot of sports franchises roll this out,” says Velazquez, who was invited to give tangible feedback about his time in the arena by the nonprofit organization called Visions. An untapped marketHistorically, watching sports has been a visual affair. You follow athletes around a racetrack. You watch a tennis ball fly across the court. But an estimated six million Americans today live with low vision—a chronic visual impairment that cannot be corrected with glasses, contacts, or medical treatments. One million Americans are legally blind. “It is an untapped market,” says Jorge Hernandez, senior technology manager at the Miami Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, who went blind at age 20. Hernandez, like several other blind or low-vision people interviewed for this article, usually listens to sports through the live radio broadcast, but he says haptic devices like OneCourt’s are one more tool in the toolbox that will make the world more accessible to people with disabilities. “We are normal individuals that live a normal life, and if you make [sports] accessible to us, guess what, we will come.” In the U.S., ADA standards stipulate that public accommodations like stadiums and theaters must ensure that people with disabilities receive effective communication through auxiliary aids or services like braille, sign language interpreters, and assistive listening devices. But according to Matthew Dietz, an expert on accessibility law from Nova Southeastern University, these standards can only evolve at the speed of technological innovation. “If sighted people see the ball around the field or a tennis court, so should the Blind,” he said in an email. “But then again, I would still prefer Phil Rizzuto calling the game.” The tipping point of innovationOneCourt is part of a growing number of startups innovating in the space. Others include the Dublin-based Field of Vision, and the French startup Touch2See. The latter has developed a tablet featuring a tactile layout of a soccer field. A moving cursor represents the position of the ball and guides your fingers on the field—a bit like an Ouija board. The Touch2See device also vibrates to signal when players are passing, shooting, or dunking. Both Touch2See and OneCourt were inspired by a viral video—potentially the same one—of a fan at a soccer match guiding the hands of their blind friend over the cardboard model of the pitch. Many of these companies are currently competing for big contracts, suggesting a growing interest from stadiums and leagues to provide accessible experiences for their fans. The Touch2See tablet made its international debut at the Paris Olympics and has since become available at the Cagliari Calcio club in Italy, FC Porto in Portugal, and many others. The company is eyeing FIFA 2026 next. “Football [soccer] is what we want to master,” Touch2See’s sales director, John Brimacombe, told me in an interview last year. In the meantime, OneCourt’s technology is quickly gaining ground in the U.S. The startup’s haptic devices first became available at a Portland Trailblazers game in 2024. They have since become available at Sacramento Kings games and Phoenix Suns home games. Ticketmaster has sponsored every partnership including at Barclays. “Our unique role in this partnership has helped build a model to quickly scale purposeful innovations from coast-to-coast,” says Marla Ostroff, managing director at Ticketmaster North America. “It’s a key step toward a more inclusive future.” Beyond basketballThe Brooklyn Nets and the Barclays Center are the first East Coast sports team and arena to provide so-called “tactile broadcasting” at home games, for free. “Having the ability for all different kinds of fans to experience the game is really meaningful for me, and this technology fit in with that perfectly,” says Keia Cole, chief digital officer at BSE, the company that owns the Brooklyn Nets, the New York Liberty, and Barclays Center. The Nets piloted the devices at the end of the NBA season, but Cole says they are planning to bring them back next season. For now, they are only available at NBA games, but they are hoping to expand to New York Liberty games, as well. WNBA uses a different kind of tracking system that OneCourt isn’t currently geared up for, but OneCourt’s COO, Antyush Bollini, says that the company started with the technology that is more widely available (Hawk-Eye) and ultimately plans on expanding to all levels of sport. “It’s only a matter of time before someday, it’s in Collegiate, and it’s in Little League games, and it’s in your rec center.” And it’s not just basketball. OneCourt has already tested its haptic devices at tennis games, baseball, and American football matches. French2See works with soccer, basketball, rugby, and various Paralympic sports like goalball and wheelchair rugby. Both OneCourt and Touch2See tablets come with a peel-off, interchangeable surface that enables teams to seamlessly switch between different sports. According to OneCourt’s CEO, Jerred Mace, any sport that is less about style (like martial arts) and more about the athletes’ location (like in swimming or racing) could be a fit. “We definitely have ambitions to get into every stadium across different sports, whether that’s MBA, WMBA, NFL, NHL, or tennis,” he says. “At the end of the day, we view this as a new standard in accessibility.” Mace came up with the idea for OneCourt while at the University of Washington. As a child, he experienced such far-sightedness that his doctor thought he wouldn’t be able to drive. His vision ended up improving through surgeries, but the 24-year-old still remembers being judged for his looks and the “goggles” he had to wear. His experience, combined with a history of disability in his family, has helped him gain deep understanding for people with disabilities. Down the line, Mace wants everyone to be able to experience sports—including fans who want to follow a game from the comfort of their own home. Velazquez, one of the blind fans who experienced the device at the Nets game last week, told me he wouldn’t necessarily use it at home. “I like [the device] for the live experience,” he says. But he was noticeably thrilled at the prospect of the technology being made available at more stadiums. His hand shot up when asked if he wanted to speak to a reporter, and his first impressions were summarized by a very spirited “amazing!” Mike Cush, chief program officer at Visions, was equally bullish. “I’m not easily impressed by technology,” he told me after trialing the device at Barclays. “But this is a game changer.” View the full article

-

Why Hyundai is doubling down on EVs—despite Trump’s war on the cars

When Hyundai recently celebrated the grand opening of its new Metaplant in Georgia, a $7 billion-plus factory that will manufacture both electric and hybrid vehicles, many lauded the South Korean automaker for its impeccable timing. The grand opening took place the same week that President Donald The President announced a slew of upcoming tariffs, including on cars and auto parts. The Georgia plant will buffer Hyundai’s electric offerings from some of those tariffs. But the outlook for auto sales in the U.S., particularly EVs, is still uncertain as The President introduces rapidly changing tariff policies and as the future of EV tax credits isn’t clear. Still, Hyundai is focused on building up its EV market. In the U.S., under the Hyundai brand, it currently offers four EVs, four hybrids, and one plug-in hybrid. Globally, it’s investing $90 billion through 2030 to bring 21 new EVs to market, and to double its hybrid offerings to 14 under its Hyundai, Kia, and Genesis brands. (At the New York International Auto Show this week, Hyundai unveiled a hybrid version of its Palisade SUV, set to arrive in the U.S. in early fall.) Hyundai aims to sell 2 million EVs annually by the end of the decade. That would mean that EVs would account for a third of the company’s total global sales. (In 2024, it sold just over 750,000.) Separate from the Georgia plant, Hyundai also recently announced a $21 billion investment to onshore U.S. manufacturing and supply chains, including for steel and EV battery components. To navigate the uncertain market, Olabisi Boyle, SVP of product planning and mobile strategy for Hyundai Motors North America, says the company focuses less on policy changes and more on consumer demand. That means offering a diversity of powertrains (internal combustion engine, battery electric vehicle, and hybrids); localizing production (Hyundai broke ground on the Georgia plant in October 2022); and staying flexible (the Metaplant was originally meant to build just EVs, but has since been expanded to include hybrids). Hyundai has also promised to keep all prices steady until June 2 amid tariff uncertainties, and Hyundai CEO José Muñoz said this week that vehicles won’t see huge price increases overnight. In 2024, Hyundai was the No. 2 EV seller in the U.S., behind only Tesla. “We are focused on that strategy,” Boyle says. “We want to be the choice if people get sick of anybody else.” Boyle recognizes that charging infrastructure and affordability are still challenges for the EV market here. As EV sales move from early adopters to the “early majority,” sales will have “a less inclined slope,” she says, meaning that growth will still happen, just at a slower rate. “And then there will be a time where that slope inclines more, and so you don’t want to be out of the game either.” In the meantime, she adds, charging infrastructure will improve and battery costs will continue to decrease, making EVs less of a compromise for buyers. Hyundai is also working to grow its EV sales across Europe to meet an EU goal requiring new cars sold by 2035 to be zero emission. To drive that growth, it now sells a compact EV called Inster that debuted in early 2025; it retails for less than $30,000. (Overall in Europe, Hyundai’s market share is around 4%. The Inster is also available in Korea, where Hyundai and Kia combined lead the EV market with a 70% share.) The Inster was named the 2025 World Electric Vehicle during the New York International Auto Show this week. Boyle couldn’t speak to whether that EV will eventually come to the U.S. market, but said, “If we think affordability is important to our customers, we’ll have products that are affordable to our customers.” There’s been a general lack of affordable EVs for U.S. buyers; 2024 research found that only 3% of U.S. EVs cost less than $37,000. Hyundai is also continuing to explore hydrogen fuel cells to add another option to its offerings, though Boyle says that may be more applicable to commercial vehicles. With a hydrogen fuel cell, an EV could fully charge in about five minutes. No matter the current uncertainties in the U.S. market, she says the EV industry is still growing globally, particularly across Europe and Asia. “It is unwise [for anyone] to say ‘just because we pull back [on EVs] we’ll be good,’” Boyle says. “You’ll be good maybe for this year. You won’t be good for 5, 10 years from now, because then the other people have taken over.” She adds: “The future will include electric vehicles. We want them to be the best electric vehicles and the best choice for the customer. That’s not going away.” View the full article

-

Analyst’s sneak peek: Inside the smart home race for service differentiation

A peek into the extensive connectivity market research to be presented by Parks Associates at WWC Mt View on April 29 - enjoy. The post Analyst’s sneak peek: Inside the smart home race for service differentiation appeared first on Wi-Fi NOW Global. View the full article

-

These diapers use plastic-eating fungi to biodegrade

When Johnson & Johnson launched the first disposable diaper in 1948, it revolutionized modern parenting. But it also, unwittingly, created an environmental disaster. Diapers are largely made of plastic, which does not biodegrade, but breaks into microplastics that pollute our waterways and end up in our food chain. And yet, more than 300,000 diapers are thrown out every minute, bound for landfills or incinerators, and accelerating climate change. There’s now a movement to design a more eco-friendly diaper, from creating easier-to-use cloth diapering systems to diapers that use less plastic. But Hiro, a newly launched startup, may have the most creative solution yet. It has launched a diaper that comes with a packet of plastic-eating fungi, which the company says will enable the diaper to biodegrade in the landfill. The startup is the brainchild of two serial entrepreneurs: Miki Agrawal, founder of Thinx period underwear and Tushy bidets, and Tero Isokauppila, founder of mushroom coffee brand Four Sigmatic. Agrawal has always been interested in tackling taboo issues, and when her son Hiro was born, she wanted to develop a diaper that was less harmful to the planet. That’s when she met Isokauppila, a Finnish entrepreneur who has devoted his entire career to making mushrooms more mainstream. A Fungi FanGrowing up, Isokauppila worked on the farm his family has tended since 1619. His work partly involved tending to mushrooms, which sparked a lifelong fascination with the plant. He went on to study fungi in college, learning about their powers as superfoods as well their ability to help other materials decompose. His knowledge of the a fungi’s nutrients to launch Four Sigmatic, which sells coffee that incorporates functional mushrooms. Now, Isokauppila is interested in how fungi can help us tackle the plastic crisis. Unlike other plants, mushrooms do not use photosynthesis to create energy. Instead, they need external food sources, and over the past 2.4 billion years they have existed, they have evolved to consume all kinds of materials. “In the earliest days of our planet’s existence, they ate rocks,” says Isokauppila. “When trees started growing, they evolved to consume trees, helping to transform them into fossil fuels.” About 15 years ago, a group of Yale undergraduates went to the Amazon and came across the first plastic-eating fungi. Plastic polymers are made of fossil fuels, and that’s a material that fungi has been interacting with for billions of years, according to Isokauppila. “My guess is that with so much plastic in our environment, fungi needed food, and plastic is fairly similar structurally to other materials it has consumed in the past,” says Isokauppila. The Plastic-Eating Hiro DiaperThere are now many scientists working on how to use fungi to process the enormous quantities of plastic in our environment, which accelerates the microplastics problem. In fact, there are already some solutions being developed. German scientists are trying to incorporate them into sewage treatment plants, while researchers from China and Pakistan identified plastic-eating fungi in a landfill in Islamabad. Even furniture companies are experimenting with additives that can help their plastic pieces degrade faster. Now Hiro is trying to use a strain of plastic-eating fungi in its diaper product. Hiro diapers themselves are fairly typical. They have the same plastic content as other premium diapers and are made in a factory in Canada that produces diapers for other brands on the market. However, in the Hiro box, each diaper comes with a little packet of plastic-eating fungi that is dormant until it comes into contact with liquid. During changing time, you simply empty the whole pouch into the dirty diaper. This begins the process of biodegrading the plastic in the diaper. The company claims that within a year, the fungi in the diaper will completely consume the plastic. Isokauppila says that the goal is to incorporate the fungi directly into the Hiro diaper itself, to make the process more convenient. But when the company did focus groups with parents, they realized that they were very concerned about product safety, particularly since diapers make direct contact with the baby’s body. “Over time, we hope that with education, we show that the fungi is perfectly safe,” he says. Another question that comes up is whether the fungi is safe when released into the environment. Will it begin eating the plastic in trash bags or items in your environment that you don’t actually want to decompose? Isokauppila says that the decomposing process is slow, taking about a year. And once it is out in the wild—such as in the landfill—it will function much like other fungi in the environment. “They are already part of nature,” he says. Making Plastic-Eating Fungi WidespreadIsokauppila believes that the Hiro diaper can be a vehicle for popularizing plastic-eating fungi. As research begins to emerge around fungi that consume plastic, we will have more scalable solutions for tackling the enormous quantity of plastic that exists on our planet. But it is possible that consumers will find these solutions scary, partly because people in Western countries are just less familiar with mushrooms and fungi than in other parts of the world. “In Asian culture and in Eastern Europe, people love mushrooms and have eaten them for thousands of years,” he says. “But in Anglo-Saxon cultures, there has been a fear of mushrooms, which is known as mycophobia.” (It isn’t clear exactly why; anthropologists suggest that it is because there is more mold in England because of the rainy weather, or because the church rejected the use of psychedelic mushrooms.) Isokauppila wants to normalize the use of fungi to break down the plastics we use at home everyday. And over time, if we are able to scale the technology used in Hiro diapers, we could reverse the damage caused by our overuse of plastic. While fungi do offer a glimmer of hope in our fight against the overwhelming plastic pollution problem, scientists say our goal should still be to cut down on our use of plastic. For one thing, we still don’t have a solution to breaking down plastic at scale. But there’s also the fact that when fungi does break down plastic, it releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change. Ultimately, our goal should be to avoid plastic entirely. But when that’s not possible—which is often—this is the next best solution. “If we can break down a diaper, we can break down anything,” he says. “Once we’ve gained enough market share, we can partner with other brands and bring this technology to the world.” View the full article

-

Lids’s new retail play: Personalized sports fandom

To make the most of its stores and keep customers coming back to shop in person, baseball hat retailer Lids announced Wednesday that 20 locations will have a newly redesigned store concept this month built for customization and personalization. Physical retail’s not dead, but to breathe new life into it—not to mention make more money from the remaining square footage—brands are rolling out more personalized in-store customer experiences. Concierge-style customer service along with customizable products have become the name of the game to counter the many headwinds physical retail has faced in recent years, including the rise of online and social media shopping, the pandemic, and inflation. Personalized experiences create upsell opportunities, strengthen customer loyalty, and, most important, draw people into those dusty physical locations. Lids does “north of 25 million transactions” in its stores, according to Glenn Schiffman, CFO of Fanatics, the apparel, merchandise, and collectibles company that owns a majority of Lids. Lids makes up a portion of the Fanatics commerce division along with Fanatics merchandise and collaborations with other brands, sports leagues, and celebrities. Its commerce division, which includes retail, is responsible for about three-fourths of its 2024 revenue, according to data from Sportico, a sports industry trade outlet. Parent company Fanatics grew 15% in 2024. At Lids, the new store concept has a build-a-hat kiosk where customers can personalize headwear digitally; select locations will also have curving stations where customers can curve the brim to their liking. Known for its officially licensed and branded hats and apparel, Lids says the new stores have an increased emphasis on local teams and exclusive products. Exclusive product drops have become a common model for brands and artists to generate hype—and sales. “Customization has always been at the heart of our brand, and this new store design takes it to the next level,” Lids President Bob Durda said in a statement. “This rollout represents our commitment to a dynamic, customer-centric experience where every visit feels personal, engaging, and tailored to each individual.” Customization at Lids gives shoppers a product that’s distinctively theirs for a premium. The store offers hat curving for $10, stitching for $12, and patches for $15. Jersey personalization, which is available in some stores, starts at $50. Sure, you could get a cheap baseball hat from Amazon, or a custom jersey through the MLB’s pricey Fanatics-run online custom shop delivered in a few days. Lids seeks to counter these offerings with a premium design built to your liking with help from a professional—and you can walk out with it the same day. Personalization also increases the likelihood of return customers. A 71% majority of consumers expect personalized interactions from companies, according to a 2021 report from consulting firm McKinsey & Co., which also states that 78% of customers are more likely to make a repeat purchase from companies that personalize their offerings. The trend toward personalized, customized retail experiences can be seen across categories, from self-service kiosks at select Pizza Hut locations to DIY AI Jibbitz for Crocs. By giving customers the opportunity to build their own custom caps, Lids is giving them a store experience worth visiting. View the full article

-

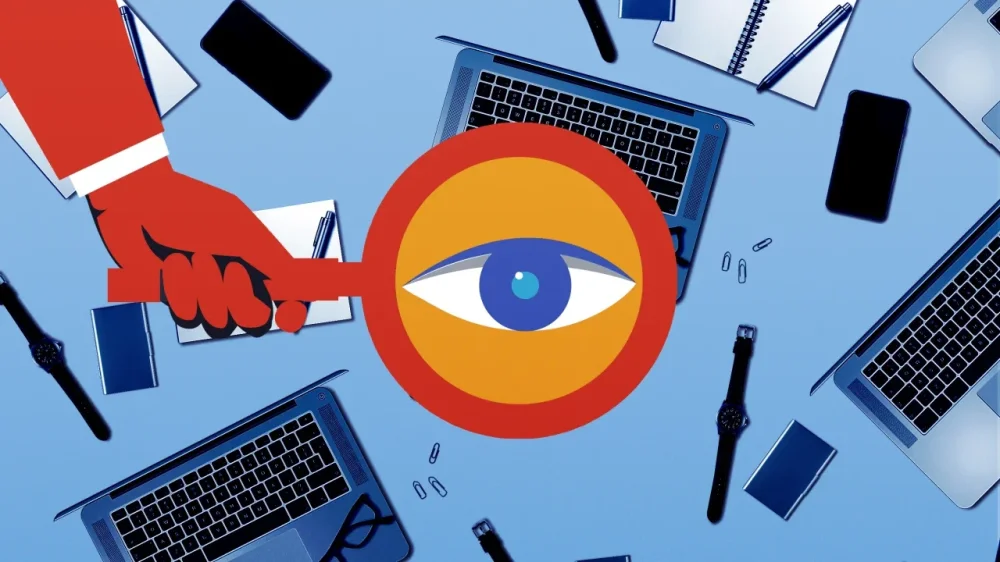

Your boss can now watch your every move. Here’s how to handle this new era of micromanaging

Having a helicopter manager can bring you down. It’s exhausting to have a boss who constantly monitors you, requires you to check in all the time, and takes away your authority to make decisions. This sort of micromanagement can lead to decreased employee morale, lower productivity, and reduced job satisfaction, according to experts. “Whether intentional or not, helicopter managers send clear signals that they do not trust their direct reports and are concerned about the work getting done correctly,” says Matthew Owenby, chief strategy officer and head of human resources at Aflac. “Helicopter managers can often exacerbate burnout by making employees feel that they are not respected, their time is not valued, and they are not given any autonomy at work. This can quickly lead to demoralization and disengagement.” It’s a growing problem, as many leaders appear to be increasing monitoring in the workplace. Owl Labs’s 2024 State of Hybrid Work Report found that 46% of workers reported that their company added or increased employee productivity and monitoring software in the past year. “This has, in part, contributed to the rise in workplace anxiety as 43% of employees say their stress levels increased compared to last year, while 55% of managers say they are more stressed than ever,” says Frank Weishaupt, CEO of Owl Labs. If you’re dealing with a helicopter manager, here are a few things experts suggest you can do: Create an accountability plan The first step is to have a direct conversation about expectations and deliverables. “I recommend focusing on establishing clear goals and metrics to shift the conversation from hours worked to results achieved,” says Weishaupt. “The goal is to shift the focus from constant surveillance to a results-oriented approach.” It’s important to set outcome-based benchmarks that give both employees and helicopter managers confidence that expectations are being met or exceeded, he explains. “This framework outlines key deliverables and success metrics that are agreed upon,” continues Weishaupt. With this understanding in place, your manager may reduce the need to hover. To start this conversation, Weishaupt suggests saying something like: “I’m committed to our team’s success and wonder if we might explore setting outcome-based benchmarks that would give both of us confidence that I’m meeting or exceeding expectations. I’d be happy to draft a proposed framework for my role that outlines key deliverables and success metrics we could review together.” Ask for feedback While your boss may have good intentions, their attitude is likely giving their reports the impression they are not trusted, or making them insecure about their abilities, says Vanessa Matsis-McCready, associate general counsel and vice president of HR Services with Engage PEO. Directly asking your boss for feedback can strengthen the accountability dynamic and cause them to lighten up. During your next check in, try asking for feedback on areas where you can improve, says Matsis-McCready. It’s also important to demonstrate that you are open to feedback. “When you ask good questions, your manager may not feel the need to hover as much,” explains Amy Morin, a psychotherapist and the author of 13 Things Mentally Strong People Don’t Do. A sample script, per Morin, could sound like this: “I want to make sure that I meet your expectations with this task. Can you share any feedback you have so far so I can make sure I’m on track and so we can address any concerns up front? I’d also like to hear your input on how you’d like to devise a plan for me to keep you updated moving forward.” This exchange may facilitate a calmer approach. “Avoid pushing back on their management style,” cautions Morin. “Instead, show that you’re looking for guidance and you’ll alleviate a lot of their fears.” And when you do get criticism, it’s important to remain diplomatic. “Avoid disagreeing with feedback even if it doesn’t sound quite right,” says Morin. “If you argue, you’ll appear defensive and they’re more likely to hover.” Proactively communicate If you take a preemptive approach to keeping your boss in the loop on your progress, this could lead to less monitoring. “Increasing the number and frequency of status reports or creating a weekly meeting, followed by a written summary of the discussion with action items and focus areas, will demonstrate to some helicopter managers that the direct report is getting their work done and managing their time successfully,” says Owenby. Seek out additional training Another thing to discuss with your boss is whether there are additional training opportunities you can pursue. Not only can these classes or training sessions boost your career, they can help increase your boss’s confidence in your skill set. Approach the training with enthusiasm, and your manager may allow more autonomy and independence. View the full article

-

This toxic chemical is leaking out of nondescript warehouses across the country. Almost no one knows about it